The Aztecs

The term, Aztec, is a startlingly imprecise term to describe the culture that dominated the Valley of Mexico in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Properly speaking, all the Nahua-speaking peoples in the Valley of Mexico were Aztecs, while the culture that dominated the area was a tribe of the Mexica (pronounced "me-shee-ka") called the Tenochca ("te-noch-ka"). At the time of the European conquest, they called themselves either "Tenochca" or "Toltec," which was the name assumed by the bearers of the Classic Mesoamerican culture. The earliest we know about the Mexica is that they migrated from the north into the Valley of Mexico as early as the twelfth century AD, well after the close of the Classic Period in Mesoamerica. They were a subject and abject people, forced to live on the worst lands in the valley. They adopted the cultural patterns (called Mixteca-Pueblo) that originated in the culture of Teotihuacán, so the urban culture they built in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries is essentially a continuation of Teotihuacán culture.

The peoples of Mesoamerica distinguished between two types of people: the Toltec (which means "craftsman"), who continued Classic urban culture, and the Chichimec, or wild people, who settled Mesoamerica from the north. The Mexica were, then, originally Chichimec when they migrated into Mexico, but eventually became Toltecs proper.

The history of the Tenochca is among the best preserved of the Mesoamericans. They date the beginning of their history to 1168 and their origins to an island in the middle of a lake north of the Valley of Mexico. Their god, Huitzilopochtli, commanded them on a journey to the south and they arrived in the Valley of Mexico in 1248. Legend has it that it was here that the Aztecs saw what was believed to be an a sign showing them that this should be the site of their future city. They saw a great royal eagle perched on the stem of a prickly pear. He had a serpent in his talons and his magnificent wings were spread against the sunrise.

According to their history, the Tenochca were originally peaceful, but their Chichimec ways, especially their practice of human sacrifice, revolted other peoples who banded together and crushed their tribe. In 1300, the Tenochcas became vassals of the town of Culhuacan; some escaped to settle on an island in the middle of the lake.

Relations between the Tenochcas and Culhuacan became bitter after the

Tenochcas sacrificed a daughter of the king of Culhuacan; so enraged were the

Culhuacans that they drove all the Tenochcas from the mainland to the island.

There, the Tenochcas who had lived in Culhuacan taught urban culture and

architecture to the peoples on the island and the Tenochcas began to build a

city. The city of Tenochtitlan is founded, then, sometime between 1300 and 1375.

The low marshes near the lake were half buried under water, so the Aztecs sank

piles into the shallows and erected their homes and floating gardens. They lived

off wild fowl and the vegetables they could raise in their gardens. This place

was called Tenochtitlan, though only known to Europeans as Mexico,

derived from their war-god Mexitli.

Conditions were far from ideal in the new settlement, and to make it worse, a

group of citizens broke off from the main group and moved to a neighboring

marsh. This resulted in domestic feuds and prevented the Aztecs from

successfully expanding into other areas. However they gradually increased in

numbers and improved their organization and military discipline, soon gaining a

fearsome reputation in the Mexican Valley for being courageous and cruel in war.

In the early part of the 1400's an event took place that changed the

circumstances for the Aztecs. The monarchy of the neighbouring city of

Tezcucan was taken over by another group The Tepanecs. This aroused a

great spirit of resistance in the prince of Tezcucan, Nezahualcoyotl, who

after much peril and some incredible escapes, mustered up enough force with the

help of the Aztecs to defeat the Tepanecs and slaughter their leader. In return

for their assistance, the Aztecs were rewarded with the conquered territories.

Then a league was formed between the neighbouring states of Tezcuco, Mexico and

the little kingdom of Tlacopan that is unparallelled in history. It was agreed

that the three states should support each other in wars and distribute the

wealth among them. This alliance soon began to spread out of the Mexican Valley

and by the middle of the 1400's, under the rule of the first Montezuma

had spread down the sides of the tableland to the borders of the Gulf of Mexico.

The Aztec capital , Tenochtitlan prospered and feuds were ended to bring the

people under one government.

The throne was filled by a succession of princes who were able to profit from their enlarged resources and the enthusiasm of the nation to engage in war. Year after year the armies returned with spoils from conquered cities and captives. No state in the Mesoamerican region was able to resist the growing strength of the conquerers. By the start of the 1500's, the Aztec dominion had spread (under the bold and bloody Ahuitzotl), across the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific and into the farthest corners of Guatemala and Nicuragua.

Social Structure

The Aztecs did have two clearly differentiated social classes. At the bottom

were the macehualles, or "commoners," and at the top the pilli, or

nobility. These were not clearly differentiated by birth, for one could rise

into the pilli by virtue of great skill and bravery in war.

All male children went to school. At the age of 15, each male child went to

telpuchcalli ("house of youth"), where he learned the history and

religion of the Aztecs, the art of war and fighting, the trade or craft specific

to his calpulli , and the religious and civic duties of everyday

citizenship. The children of nobility also attended another school, a school of

nobility or calmecac , if he was a member of one of the top six

calpulli . There the child learned the religious duties of priests and its

secret knowledge; for the distinction between government and religious duties

was practically non-existent. This public education was only limited to boys.

In Aztec society, women were regarded as the subordinate of men. Above

everything else, they were required to behave with chastity and high moral

standards. For the most part, all government and religious functions were closed

off to women. In fact, one of the most important religious offices, the Snake

Woman, was always filled by men. There were some temples and gods that had

priestesses, who had their own schools, but their exact position in the

hierarchy is unknown.

Aztec laws were simple and harsh. Almost every crime, from adultery to

stealing, was punished by death and other offenses usually involved severe

corporal punishment or mutilation (the penalty for slander, for instance, was

the loss of one's lips). This was not a totalitarian state, however; there was a

strong sense of community among the Aztecs and these laws, harsh as they seem,

were supported by the community rather than an autocratic judiciary.

Religion

The religion of the Aztecs was incredibly complicated, partly due to the fact

that they inherited much of it from conquered peoples. Their religion was

dominated by three gods: Huitzilopochtli ("hummingbird wizard,"

the native and

chief god of the Tenochca, Huitzilopochtli was the war and sun god),

the native and

chief god of the Tenochca, Huitzilopochtli was the war and sun god),

Tezcatlipoca ("Smoking Mirror," chief god of the Aztecs in general) ,

,

and

Quetzalcoatl ("Sovereign Plumed Serpent," widely worshipped throughout

Mesoamerica and the god of civilization, the priesthood, and learning). Below

these three gods were four creating gods who were remote and aloof from the

human world.

("Sovereign Plumed Serpent," widely worshipped throughout

Mesoamerica and the god of civilization, the priesthood, and learning). Below

these three gods were four creating gods who were remote and aloof from the

human world.

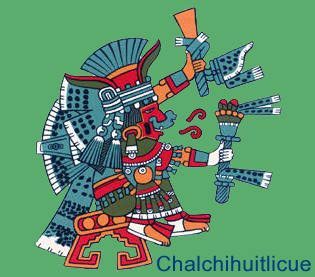

Below these were an infinity of other gods, of which the most important were Tlaloc, the Rain God,

important were Tlaloc, the Rain God,

Chalchihuitlicue, the god of growth,

and Xipe, the "Flayed One," a god associated with spring.

While human sacrifice was the most dramatic element of Aztec sacrifice, the

most common form of sacrifice was voluntary blood-letting which occurred at

every religious function. Such blood-letting was tied to rank: the higher one

was in social or priestly rank, the more blood one had to sacrifice.

There was an urgency to all this sacrifice. The Aztec believed that the world

was controlled by divine forces that were in constant conflict and opposition to

one another. The universe was poised between conflicting forces of creation and

destruction; human beings could, in part, influence this balance through the

practice of sacrifice.

In addition to sacrifice, the Aztec religion, like the Mayan religion, was

dominated by calculations of time. The Aztecs had several calendars; each day

was controlled by two gods, each of which had a benificient and a malevolent

aspect. In a complex series of astronomical calculations, one could precisely

determine how to behave and what to do in order to achieve the best results.

It is not unfair to say that Aztec culture was overwhelmingly

eschatological in a way that can only be rivaled by early Christianity. The

Aztecs, like the Mayans, believed that the universe had been created five times

and destroyed four times; each of these five eras was called a Sun. The

first age was called Four Ocelot (for it began on the date called Four Ocelot).

Tezcatlipoca (Smoking Mirror) dominated the universe and eventually became the

sun disk. The world was destroyed by jaguars. The second age was Four Wind,

dominated by Quetzalcoatl (Sovereign Plumed Serpent); men were turned to monkeys

and the world was destroyed by hurricanes and tempests. The third age was Four

Rain, dominated by Tlaloc (the rain god); the world was destroyed by a rain of

fire. The fourth era was Four Water and was dominated by Chalchihuitlicue (Woman

with the Turquoise Skirt); the world was destroyed by a flood.

The fifth era,

the one we live in now, is Four Earthquake, and is dominated by Tonatiuh, the

Sun-God. This age will end in earthquakes. (see right)

The fifth era,

the one we live in now, is Four Earthquake, and is dominated by Tonatiuh, the

Sun-God. This age will end in earthquakes. (see right)

The Aztecs had two calendars: the ritual year and the solar year. The ritual

year lasted for 260 days and the solar year lasted for 365 days. Every fifty-two

years these two calendars would resynchronize; the Aztecs, then, lived in

52-year cycles. In Aztec religion, the destruction of every era always occurred

on the last day of each 52 year cycle (although each era lasted for several of

these cycles). Every 52 years, then, the Aztecs believed that the world was

about to end and the close of the 52 year cycle was the most important religious

event in Aztec life for this period was the most dangerous period in human life.

This was the time when the gods could decide to destroy humanity. Every cycle

ended with the New Fire Ceremony. For five days before the end of the cycle, all

religious altar fires were extinguished and people all over the Aztec world

destroyed furniture and possessions and went into mourning for the world. On the

last day, the priests went to the Hill of the Star, a crater in the Valley of

Mexico, and waited for the constellation of the Pleiades to appear. If it

appeared, that meant that the world would continue for fifty-two more years. The

priests would light a fire in an animal carcass, and all the fires of the Valley

of Mexico would be lit from this single fire. The day after saw sacrifices,

blood-letting, feasting, and renovation of possessions and houses.

The Aztecs had two calendars: the ritual year and the solar year. The ritual

year lasted for 260 days and the solar year lasted for 365 days. Every fifty-two

years these two calendars would resynchronize; the Aztecs, then, lived in

52-year cycles. In Aztec religion, the destruction of every era always occurred

on the last day of each 52 year cycle (although each era lasted for several of

these cycles). Every 52 years, then, the Aztecs believed that the world was

about to end and the close of the 52 year cycle was the most important religious

event in Aztec life for this period was the most dangerous period in human life.

This was the time when the gods could decide to destroy humanity. Every cycle

ended with the New Fire Ceremony. For five days before the end of the cycle, all

religious altar fires were extinguished and people all over the Aztec world

destroyed furniture and possessions and went into mourning for the world. On the

last day, the priests went to the Hill of the Star, a crater in the Valley of

Mexico, and waited for the constellation of the Pleiades to appear. If it

appeared, that meant that the world would continue for fifty-two more years. The

priests would light a fire in an animal carcass, and all the fires of the Valley

of Mexico would be lit from this single fire. The day after saw sacrifices,

blood-letting, feasting, and renovation of possessions and houses.