Galvez |

|

|||

|

The Regiment of Louisiana and the Spanish Army in the American Revolution By Thomas E. DeVoe and Gregory J. W. Urwin THE CAMPAIGNS OF BERNARDO DE GALVEZAs noted editor and Revolutionary War scholar

Greg Novak has so astutely put it, most Americans view their War of'

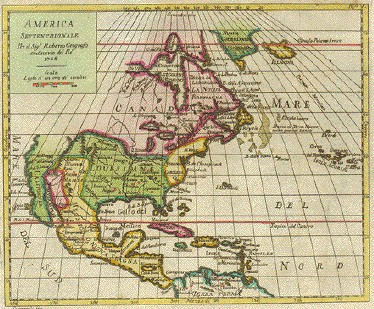

Independence simply Much has been made of the military and economic help France so generously supplied to the struggling United States, but the many notable contributions of France's Bourbon ally, the resurgent Spain of Charles III, have been virtually ignored. When the widening breach that had been growing between the Thirteen Colonies and the Mother Country exploded into a full-fledged rebellion in the spring of 1775, both the courts at Versailles and Madrid hailed the event as a godsend. Here was their chance to strike at their ancient enemy while her arms were tied and get some revenge for the humiliating defeats England had dealt them during the Seven Years War. Trading Companies France and Spain each set up bogus trading companies to send the American Rebels covert shipments of arms, clothing, munitions and other much-needed items, and they loaned the impecunious Continental Congress thousands of dollars. Somewhat to Madrid's dismay and displeasure, the French were a little too generous and friendly with the Americans. They gave the Rebels thirteen times as much money and material assistance as their Iberian cousins, and then in 1778, France actually signed an alliance with the United States and entered the war as an official belligerent. Spain hesitated at taking such a plunge. She was glad to help the Yankees tweak the British lion's tail, but as a leading imperial power herself, she did not want to give her Creoles the idea that she approved of so dangerous an idea as colonial insurrection. When Madrid finally decided to declare war on England in the summer of 1?79, it was not because Charles III and his advisors had undergone a sudden conversion to the cause of American liberty, but because they felt it was in the best interests of their country. France had promised to cooperate militarily in the recovery of Florida, the Bay of Honduras, Minorca, and Gibraltar, if Spain openly entered the struggle against the British. It was too good an offer to refuse. France clearly overshadowed Spain in the sheer weight of her direct aid to the struggling new nation, and she easily outdid her Bourbon ally in exhibitions of friendship for the Rebels. No Spanish regiments served side-by-side with the Continentals as the French did at Newport, Savannah and Yorktown, but it would be a mistake to conclude that Spain had a negligible effect on the outcome of the conflict. Spain sent the United States hundreds of muskets, thousands of coats, small clothes, blankets, shirts and shoes, and vast amounts of gunpowder, naval stores, copper, tin, brass cannon and horse furniture. Supplies and money channeled by Spanish officials through New Orleans and St. Louis enabled George Rogers Clark to safeguard Kentucky and sweep the British from much of the Northwest Territory. Even though Spain committed the bulk of her naval and military power to the abortive, four year siege of Gibraltar, at various times between 1779 and 1781, at least 17,000 Spanish soldiers and sailors saw service on what was to become American soil, capturing a number of English garrisons in the process and seizing the province of West Florida for their monarch. The man who was almost solely responsible for this triumph of Spanish arms was Bernardo de Gálvez, a young professional soldier born in 1746, the captain of the grenadiers of the Regiment of Seville, the colonel of the Fixed Infantry Regiment of Louisiana, and the Governor of Louisiana from 1777 to his premature death in 1786. When the Spanish Court informed its colonial administrators on May 18, 1779, that it intended to declare war on Great Britain by the twenty-first of June, young Gálvez realized that weeks would pass after that before the English commanders in North America learned of the commencement of hostilities. He decided to utilize that period of grace to surprise and seize the enemy forts facing his province on the Mississippi River. On August 27, 1779, Gálvez launched the first of his three brilliant campaigns. A violent hurricane had devastated his base at New Orleans only nine days before, spoiling, sinking or washing away nearly all the provisions and boats the enterprising governor had assembled for his expedition with such great difficulty. Undeterred by this grave setback, Gálvez quickly made good his losses or did without, and set out only four days after his originally intended date of departure. Gálvez marched out of New Orleans at the head of 170 veteran regulars drawn from the Regiments of Spain, Mallorca, Havana and Prince, 330 untested recruits from his own Regiment of Louisiana, twenty carabiniers, sixty white militiamen, eighty free blacks and mulattoes, and seven American volunteers. As they tramped along the Mississippi shore, they were accompanied by a flotilla of flatboats bearing four 4-pounders, one 24-pounder, and five 78-pounders. Forging on ahead, Gálvez mustered 600 additional men from the Acadian and German settlements and 160 Indians, bringing his hodgepodge force up to a grand total of 1,427 men-at-arms. The Spanish troops covered 105 miles in eleven days, losing at least a third of their number along the way to fatigue and disease before they caught sight of the first enemy post at the village of Manchac. At dawn the next day, September 7, Gálvez's militia rushed Fort Bute and took it from its shocked, twenty-seven man English garrison without the loss of a single Spaniard. Resting his soldados a few days, Galvez then pushed on to Baton Rouge, which was defended by 146 Redcoats, 201 Waldeckers, 11 Royal Artillerymen and 150 armed settlers and Negroes shielded by the walls of a stout fort with thirteen guns. By the time he reached there, September 12, fever and privation had pared his dwindling army down to 384 regular infantry, 14 artillerymen and 400 militia, Indians and Negroes. Utilising a clever ruse on the night of the twentieth, Gálvez was able to place a battery unseen within musket shot of the British fortifications. At 5:45 A.M. the next day, the Spanish guns began to blast the palisade to splinters and level the earth-works. The English took this punishment for three and a half hours, and then they raised the white flag. Included in the capitulation agreement was the surrender of 80 Waldeck grenadiers staffing Fort Panmure at Natchez. Captured Totals In the matter of just a few weeks, Colonel Gálvez and his motley army had captured 550 British and German regulars, 500 armed settlers and Negroes, and three forts. They had added 1,290 miles of the best land along the Mississippi to their sovereign's domain, and all at the ridiculously low cost of one Spaniard killed and two wounded. It had been a brilliant coup, but Gálvez was just getting started. He had been maintaining an effective espionage service in British territory since 1777, and his spies told him that the rest of West Florida was ripe for the plucking. Some fresh troops had been sent to New Orleans while Gálvez had been absent on his first sortie, and the young governor decided to incorporate them into his new expedition. On January 11, 1780, he embarked 754 men aboard twelve small vessels at New Orleans and set sail for Mobile. Gálvez's new force consisted of 43 soldiers of the Regiment of the Prince, 50 of the Regiment of Havana, 141 of the Regiment of Louisiana, 14 artillerymen, 26 carabiniers, 323 white militia, 107 free blacks and mulattoes, 24 slaves and 26 Americans. At the same time he sent an officer to Havana to request an additional 2,000 reinforcements from his immediate superior, the Captain-General, but all the troops that esteemed gentleman would spare were the 567 regulars of the Regiment of Navarro. Under Gálvez's handling, however, they were enough to turn the trick. On March 14, the 98 Royal Americans, 4 Maryland Loyalists, 60 sailors, 54 militia and 51 armed Negroes that composed the garrison of Mobile's Fort Charlotte left their works and grounded their arms after a two week siege. King Charles III was so delighted by his young servant's string of daring victories that he appointed him "Governor of Louisiana and Mobile" and raised him to the rank of "Field Marshall in command of Spanish operations in America." Armed with the royal favor and fiat, Gálvez sped down to Cuba in August 1780 to personally raise the ships and soldiers he needed to besiege Pensacola, the capital of British West Florida. On October 16, 1780, Gálvez sailed proudly out of Havana Harbor with 7 warships, 5 frigates, 1 packet boat, 1 brig, 1 armed lugger and 49 transports containing 164 officers and 3,829 regulars. A savage tropical storm struck the fleet on the 18th and scourged it for five days, sinking one ship and scattering the rest across the Gulf of Mexico. Refusing to admit defeat, Gálvez put back to Cuba and regrouped his command. At the end of February 1781 he set out again, and this time everything went right. Sighting Pensacola on March 8, the following night Gálvez loaded a party of grenadiers and light infantry into some ships' boats and occupied Santa Rosa Island at the entrance of the bay before the English even knew they were there, In the next few weeks naval and military reinforcements materialized from Spain and various quarters of her empire. By the end of April, Gálvez had shifted his operations to the mainland and had pushed his trenches and batteries to within half a mile of Fort George, the refuge of Pensacola's harried defenders, 1,600 Redcoats, Hessians, Loyalists, Sailors, Negroes and Militia. Facing them were at least 7,000 of Spain's finest soldiers from such outfits as the Fixed Battalion of Louisiana, the Regiments of the King, the Crown and the Prince, the Royal Corps of Artillery, the Regiments of Spain, Soria, Navarro, Guadalajara, Mallorca, Navarra, Aragon, Cataluna, Volunteers, and Toledo, the Fixed Battalion of Havana, and the three tough red-coated regiments of Spain's famous Irish Brigade, the Hibernia, Irlanda and Ultonia. Some 1,350 Spanish sailors were put ashore to man some big guns and serve as laborers. Another 10,000 seamen in sixteen ships-of-the-line and dozens of smaller craft hovered offshore, cutting off all chance of escape or relief from the sea. Four French frigates arrived to add 725 allied troops, light infantrymen from the Regiment of Orléans, piguets from the Regiments of Poitou, Agenois and Gâtinais, and assorted artillerymen, to Gálvez's swelling host. Pensacola's fate was sealed, but the end came in a dramatic climax on May 8, when a single Spanish cannonball entered a British powder magazine and sent eighty to one hundred members of the 1st Battalion of Pennsylvania Loyalists flying sky high in an earth-shaking explosion that gutted the Queen's Redoubt, which held a stretch of high ground overlooking Fort George. Some quick-thinking Spanish light infantry seized the shattered, smoking earthworks, with its ghastly, shredded bodies, and brought a couple of howitzers and field-pieces directly to bear on the now exposed enemy lines. At 3:00 P.M. the surviving 1,113 men of the British garrison acknowledged the inevitable and surrendered, West Florida was Spanish again. The conquests of Bernardo de Gálvez secured the province of Louisiana, the Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast for the Spanish Empire. England was so shaken by the defeats she sustained at his hands that she also ceded East Florida to his royal master and abandoned the trans-Appalachian region to be divided between Spain and the infant United States. Thanks to his amazing courage, foresight, guile, and iron determination, young Gálvez proved that it was indeed possible for one man to change the course of history. THE REGIMENT OF LOUISIANAThe backbone of Gálvez's campaigns against Manchac, Baton Rouge and Mobile, and the first line of defense in his far-flung province, was El Regimiento Fijo de Infanteria de la Luisiana, or the Fixed Infantry Regiment of Louisiana. After certain reforms proposed in 1764, Madrid employed two types of regular units to defend the wide expanses of the Viceroyalty of New Spain and her extensive holdings in South America. First there were the peninsular regiments, which were recruited in Spain or elsewhere in Europe, and were rotated on overseas service in the principal ports and frontier presidios. The second category consisted of fijo regiments - permanent or fixed battalions raised in the colonies themselves and kept there, The Regiment of Louisiana belonged to this latter class. The Regiment of Louisiana was founded in 1769 by General Alejandro O'Reilly, Charles III's best military commander, after he crushed a French rebellion against Spanish rule at New Orleans with an awesome punitive expedition of 2,056 troops and 24 ships. Before O'Reilly pulled out of the pacified city, 179 men from the Regiment of Lisbon and some pickets from the Regiments of Guadalajara, Aragon and Milan volunteered to form the nucleus for Louisiana's new fixed battalion. Like many other colonial organizations, the Regiment of Louisiana never reached the paper strength specified by the Spanish Army's 1768 regu1ations. By the spring of 1779, when Spain finally decided to declare war on the English, the Louisiana had only five companies. Each company was supposed to average one captain, three lieutenants, three sergeants, seven corporals, seventy-nine privates and two drummers. In July of that year 159 recruits from Mexico and the Canary Islands joined Gálvez at New Orleans. This gave the regiment enough men to expand to a respectable eight companies. Only about 380 of the Louisiana were concentrated under the colonel's direct control at New Orleans. However, the rest were scattered far upriver and stationed at such remote spots as St. Louis, Arkansas Post, Upper Illinois, and Balize. The regimental coat, or la casaca, of the Louisiana Regiment was white, which had been the official color of the Spanish line since the accession of the Bourbon dynasty early in the eighteenth century. While peninsular troops were sent to campaign in the tropics in heavy European wool, thanks to supply difficulties and perhaps a touch of common sense, the fixed battalion was issued regimentals made out of lighter cotton or linen - with the latter being more common. In 1770 Charles III had his army adopt the more modern military fashions decreed by his French cousin, but even as late as 1779, the troops of the Louisiana were wearing the old long style coat. These garments were lined with blue cloth. They also had blue cuffs and collars, which were detachable so as to not run and contaminate the white shell and sleeves during the frequent launderings that were necessary to keep such items clean. The repeated washings helped the facings and turnbacks quickly fade to a mellow sky blue. The regimental was single-breasted and had ten large pewter buttons on the right side. They were plain, flat and one inch in diameter. Three buttons were attached to each of the coat's two pockets and two more sat at about waist level above the tails. The Louisiana Regiment's small-clothes were supposed to be blue, but frequent shortages dictated that white cotton be substituted, which frequently happened to the linings of the regimental coat as well. The long waistcoat, or "el chaleco", had sleeves. It was closed by a single row of half-inch pewter buttons. Three more buttons were sewn by each pocket and one at the opening of each sleeve. Gálvez intended his regiment's coats to last three years apiece, and so the troops were allowed to turn out for fatigue and drill, and even on garrison duty, when the weather was particularly hot, in just their sleeved waistcoats. They were also permitted to wear them while on campaign or in battle. The Spanish Army's shirt was made out of the standard fine white linen and had the usual high collar. Instead of a neck-stock, the soldado wrapped a white linen cravat two inches wide and thirty inches long around his neck. Spanish troops were issued two kinds of canvas gaiters. There was a white pair that fitted over the knee and each was fastened on the outside of the leg by a row of sixteen small, cloth-covered buttons. A black leather strap was attached to the bottom of the inside of the legging, run under the instep of the shoe and attached to the fourth or fifth button to keep it in place. A shorter black pair with only eight small white-metal buttons apiece, also saw service with the Louisiana. These leggings protected the soldiers' white worsted stockings and the brass buckles on their plain black shoes. The Regiment of Louisiana was apparently issued a bewildering variety of firelocks. Most of the men probably carried the 1752 Spanish Fusil, a brass-banded weapon modelled after the French musket of the time. Its straight, broad-based bayonet was housed in a dark leather scabbard that hung from a brown or buff waistbelt or a crossbelt slung over the left shoulder. There is evidence that many Spanish troops carried French muskets, and some British flintlocks were also turned on their former owners. In the Louisiana Regiment musket slings were made out of buckskin or natural leather, and even linen, when supplies of the other two materials were short. A plain black cartridge box rested on the right hip from a narrow buckskin or dark leather strap slung from the right shoulder. This cartuchera had two flaps to keep rain water from spoiling the cartridges inside, and it was joined to the strap by two brass rings. Some of the troops may have also gone into action still using the old twenty-one round belly box, which was attached to the waistbelt. The Royal Arms was embossed on the outer flap and highlighted by red paint. Battalion company soldiers wore a black tricorne hat. It was made of stiffened black felt and edged with white tape. A red satin cockade was fixed on the left side of the front corner by a gold loop. Members of the grenadier company wore a tall, sloping bearskin cap that was entirely plain except for a blue crown in the back with a white-laced cape (bag) that flowed down to the shoulder. All the men had a cloth fatigue or barracks cap, which was known as the bonnet du police or el garro de guartel. It was made of blue and white wool with a blue tassel. A brass plate cut in the shape of the regimental coat of arms was mounted on the front of the cap. Non-commissioned officers and grenadiers were issued a short, curved saber with a plain brass hilt and guard. It was carried in a black leather scabbard that hung from a double frog with the owner's bayonet. Grenadiers also had brass matchboxes attached to the upper front of their cartridge box belts. The colonial Spanish soldier had a wide range of vessels to choose from for his canteen. Leather bags, dried gourds, leather-covered bottles and little wooden kegs were all pressed into service. His blanket, rations and other equipment and belongings were crammed into a combination knapsack/ haversack that came in the form of a heavy linen bag or a leather bag that was held on the back with a brown leather sling that slipped across the front of the body over the right shoulder. The soldado's hair was cut short on top of the head and gathered into a single tight curl on each temple. The rest was braided in a long, sixteen-inch queue that was wrapped in a black satin ribbon that came to a large bow at the collar of the coat. The tip of the queue reached down to the junction of the cross-belts on the soldier's back. Officers had silver buttons and hat lace. When on duty they wore plain gorgets so close to their throats they were obscured by the collars of their coats. As the colonel of the regiment, Gálvez carried a regulation command stick with a golden knob and tassel. At the edge of the cuffs on his regimental, he had three strips of silver lace to mark his rank. In keeping with the custom of the day, the musicians of the Regiment of Louisiana had quite distinctive uniforms. The collar, cuffs, pocket flaps, turnbacks and front of the coat and the waistcoat were edged in white and red chequered lace. Sources disagree on precisely how this brilliant color scheme was effected. Some say that a row of red crosses was superimposed over white lace, and others believe that there were white crosses over a red background. The drummers carried instruments with blue shells and red rims. The royal coat of arms was centred at the front of the drum. BIBLIOGRAPHYBooks Archer, Christen I. The Army in Bourbon Mexico,

1760-1810. Albuquerque. University of New Mexico Press, 1977. Articles Beer, William. "The Surrender of Fort

Charlotte, Mobile, 1780." American Historical Review. Vol. 1 (July

1896), pp. 696-99. |

as a private little family quarrel between their forebears and England. In

reality, however, it was one of the world's first truly global war, and it

was the intervention of three major European powers, as well as the

frequently celebrated and sometimes overrated courage and persistence of

George Washington and the Continental Army, that brought Great Britain to

terms in 1783.

as a private little family quarrel between their forebears and England. In

reality, however, it was one of the world's first truly global war, and it

was the intervention of three major European powers, as well as the

frequently celebrated and sometimes overrated courage and persistence of

George Washington and the Continental Army, that brought Great Britain to

terms in 1783.