|

|

||||

|

||||

Texas History: A Summary

Mid-1519 -- Sailing from a base in Jamaica, Alonso Alvarez de Pineda, a Spanish adventurer, was the first known European to explore and map the Texas coastline

When Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca was shipwrecked along the Texas coast in 1528, he and three surviving shipmates became the first Spaniards to explore the territory that would become Texas. Cabeza de Vaca and his companions lived among the Native Americans for eight years before returning home to what is now Mexico.. They took with them tales of cities of gold that caused great excitement.

In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado set off with an army to find the fabled cities of gold. Coronado searched all the way to present day Kansas without ever finding the wealth described by Cabeza de Vaca.

In 1682, Frenchman Rene Robert Cavlier, Sieur de La Salle, followed the Mississippi River to its mouth and claimed all of the country that was drained by the great river for France. he called the area Louisiana, which included the territory of Texas. IN 1685, La Salle established a crude stockade, Fort St. Louis, on the Texas cost. But in 1690 Spaniard Alonzo de Leon discovered that Native Americans had destroyed the fort and La Salle had been assassinated by one of his own men in 1687. The French flag flew over Texas for only five years, from 1685 until 1690, before the land once again became the property of Spain.With the threat of the French removed, the Spanish immediately began establishing missions in East and central Texas. Along the San Antonio River, five missions still stand as testament to the Spanish heritage of Texas. financed by the Spanish government and directed by Franciscan friars between 1680 and 1773, the missions were civil as well as spiritual centers. Each mission was designed as a self-contained village, with a fortified wall surrounding a central plaza. The Alamo is the most famous of the missions. but the Mission San Jose is the state's largest restored mission. Mission Concepcion, established in 1731, remains virtually untouched by any restoration, and original, slightly faded frescoes adorn the walls. Between Mission Espada and Mission San Juan Capistrano, a water system considered one of the oldest in the United States still carries water. More than 30 missions were established by the Spanish in Texas.

In 1731 the city of San Fernando de Béxar,qv as San Antonio was then called was established by Canary Islanders brought in for that purpose.

In 1803, when France sold Louisiana to the United States, and Texas found

itself on the border of New Spain (present day Mexico) and the United States.

The Spanish intended to colonize the territory with loyal subjects and keep out

the land hungry Americans. but in 1821, Spain gave Stephen F. Austin permission

to bring American families into the territory. That small crack in the border

would lead to the Anglo-American settlement of Texas. Austin's colonists began

arriving in 1823, only to find that Mexico had won its independence from Spain..

The Territory was now the Mexican state of Coahuila-Texas.

The colonization of Texas as a Mexican state brought Anglos westward from the United States and Mexicans northward. Differences in language and culture led to tension. Most Mexicans were Catholic and most Anglos were Protestant. The Americans felt ties to the United States, not Mexico. Trade grew between Texas and the United States, alarming Mexico. In 1830, the Mexican Congress passed a law that stopped American immigration into Texas. it initiated custom collections as the government tried to stay in control. Dissatisfaction spread among the settlers, and in 1832, skirmishes broke out that signaled the coming revolution.

The Texas Revolution lasted from October, 1835 until the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

War broke out in Gonzales on October 2, 1835, when Mexican troops attempted to confiscate a cannon from Texas settlers. Waving a banner that read, "Come And Take It," the Texans defeated the Mexicans.

PROVISIONAL GOVERNMENT.

The provisional government set up by the Consultation was the only governing body in Texas from November 15, 1835, until March 1, 1836, but during much of the period it was inactive. Henry Smith, a leader of the independence or war party and an opponent of the Declaration of November 7, 1835, was made governor; James W. Robinson, also of the independence party, was lieutenant governor. Most of the members of the legislative body, the General Council, were from the peace party, which was opposed to an immediate declaration of independence and inclined to quarrel with Smith and oppose his plans. Personalities entered into the dispute, and after about a month the governor and the council quarreled bitterly. There was no agreement as to the powers of the governor. The council wished to cooperate with Mexican liberals; Smith wished to ignore the Declaration of November 7 and proceed as though Texas were an independent state. The most important single cause of trouble was the proposed Matamoros expedition. As a result of the various controversies, the governor made an attempt to dissolve the council, which retaliated by impeaching Smith and recognizing Robinson as head of state. For all practical purposes the provisional government then ceased to exist, and Texas was without leadership during the critical month of February 1836.

The government failed because the men responsible for it lost sight of the welfare of Texas in their personal quarrels. The shortsighted Consultation placed the government in the hands of incompetent officials with opposing views and deprived Texas of the services of its ablest men, among them Stephen F. Austin, William H. Wharton, and Branch T. Archer, who were sent as commissioners to the United States, and Sam Houston, who was made commander in chief of a nonexistent army. The ad interim government was established after the signing of the Declaration of Independence on March 2, 1836.

Santa Anna surrounded the Alamo on February 23, 1836. He finally attacked n March 6. All of Texas' 187 men died in the battle, including David Crockett, James Bowie, and William Travis. Toribio Losoya, a 27 year old who was born at the Alamo compound, was one of eight native born Mexicans who fought on the side of Texas. The four corners of the church crumbled, and Santa Anna burned the interior. Yet the church's front limestone wall survived with its delicate carvings intact. Over the arched doorway of the Alamo, the keystone still bears the carving of the royal seal of the Spanish Crown.

On April 21, 1836, Sam Houston and his Texas forces defeated Mexican troops at the Battle of San Jacinto. It was the Texas Revolution's decisive battle and lasted a short 18 minutes. Houston attacked the Mexicans during the afternoon while Santa Anna, the Mexican president, was taking his siesta. When the smoke cleared, Santa Anna was nowhere in sight, and Houston dispatched patrols to find the Mexican general. While on patrol, James Sylvester spotted a group of deer grazing in the grass. The Kentucky sharpshooter leveled his gun, but a movement nearby spooked the animals. When Sylvester went to investigate, a Mexican in a dirty hat bolted from the grass only to fall flat on his face in front of his captors. As the patrol rode back into camp with their catch, Mexican prisoners began shouting, "El Presidente!" James Sylvester had captured Santa Anna.

Texas as a Republic

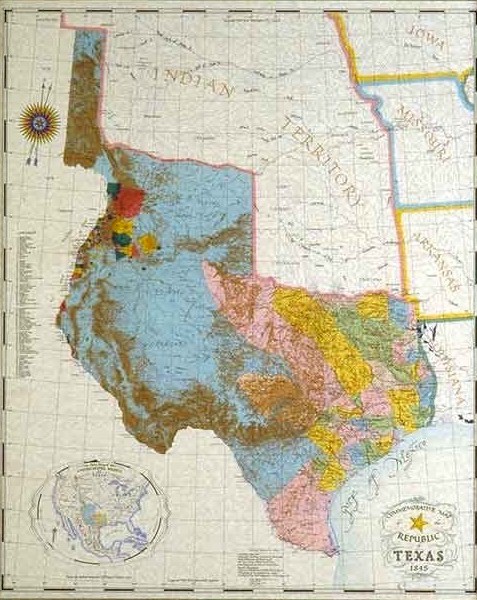

When

Texas declared independence from Mexico in 1836, the land grab was on and Texans

quickly claimed territory for their new republic. from the headwaters of the Rio

Grande in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado, the western boundary stretched

north to the 42nd parallel in Wyoming and followed the Rio Grande south through

New Mexico to the Gulf of Mexico. the Sabine River set the eastern boundary. The

northern border meandered along the red River tot the 100 degree meridian, then

extended into present day Kansas. From there, the Arkansas River set the

boundary into central Colorado. A long arm of territory reached into Wyoming

When

Texas declared independence from Mexico in 1836, the land grab was on and Texans

quickly claimed territory for their new republic. from the headwaters of the Rio

Grande in the San Juan Mountains of Colorado, the western boundary stretched

north to the 42nd parallel in Wyoming and followed the Rio Grande south through

New Mexico to the Gulf of Mexico. the Sabine River set the eastern boundary. The

northern border meandered along the red River tot the 100 degree meridian, then

extended into present day Kansas. From there, the Arkansas River set the

boundary into central Colorado. A long arm of territory reached into Wyoming

On March 1 George C. Childress, who had recently visited President Jackson in Tennessee, presented a resolution calling for independence. At its adoption, the chairman of the convention appointed Childress to head a committee of five to draft a declaration of independence. When the committee met that evening, Childress drew from his pocket a statement he had brought from Tennessee that followed the outline and main features of the United States Declaration of Independence. The next day, March 2, the delegates unanimously adopted Childress's suggestion for independence. Ultimately fifty-eight members signed the document. Thus was born the Republic of Texas.

The convention declared all able-bodied men ages seventeen to fifty liable for military duty and offered land bounties of 320 to 1,280 acres for service from three months to one year. Those men who left Texas to avoid military service, refused to participate, or gave aid to the enemy would forfeit their rights of citizenship and the lands they held in the republic. The convention also halted public land sales and closed the land offices. It authorized its agents in the United States to seek a $1 million loan and pledge land for its redemption. With the declaration of independence, the chairman appointed one person from each municipality to a committee to draft a constitution. If one individual can be designated the "father of the Texas Constitution," it should be David Thomas, who chaired the committee, spoke for the group, and put the draft together. The convention adopted the document about midnight on March 16.

The Constitution of the Republic of Texas was patterned after that of the United States and several Southern states. It provided for a unitary, tripartite government consisting of a legislature, an executive, and a judiciary. The arrangement was more like that of a state than a federal system of states bound together by a central government. The document specified that the president would serve three years and could not succeed himself in office. He would be the commander in chief of the army, navy, and militia, but could not "command in person" without the permission of Congress. There would be a two-house Congress. The House of Representatives would comprise from 24 to 40 members until the population reached 100,000; thereafter the number of seats would increase from 40 to 100. Members would serve one-year terms. The number of seats in the Senate would be "not less than one-third nor more than one-half that of the House." Senators were to serve three-year overlapping terms, with one-third elected each year. The constitution legalized slavery but prohibited the foreign slave trade. Immigrants from the United States could bring slaves with them. Free blacks could not live in Texas without the consent of Congress. No minister of the Gospel could hold public office. The constitution also contained a bill of rights. An ad interim government would direct affairs until general elections were possible.

With news that the Alamo had fallen and Mexican armies were marching eastward, the convention hastily adopted the constitution, signed it, and elected an ad interim government: David G. Burnet, president; Lorenzo de Zavala, vice president; Samuel P. Carson, secretary of state; Thomas J. Rusk, secretary of war; Bailey Hardeman, secretary of the treasury; Robert Potter, secretary of the navy; and David Thomas, attorney general. The delegates then quickly abandoned Washington-on-the-Brazos. The government officers, learning that Houston's army had crossed the Colorado River near the site of present La Grange (Fayette County) on March 17 and was retreating eastward, fled to Harrisburg and then to Galveston Island. With news of the Texan victory at San Jacinto, the Burnet government hastened to the battlefield and began negotiations to end the war. On May 14 at Velasco, Texas officials had Santa Anna sign two treaties, one public and one secret. The public treaty ended hostilities and restored private property. Texan and Mexican prisoners were to be released, and Mexican troops would retire beyond the Rio Grande. By the terms of the secret treaty, Texas was to take Santa Anna to Veracruz and release him. In return, he agreed to seek Mexican government approval of the two treaties and to negotiate a permanent treaty that acknowledged Texas independence and recognized its boundary as the Rio Grande. Military activity continued briefly along the Gulf Coast. On June 2 Maj. Isaac W. Burton, leading twenty mounted rangers, contacted a suspicious vessel in Copano Bay and signaled the vessel to send its boat ashore. His men captured the vessel, named the Watchman, and found it loaded with supplies for the Mexican army. On the seventeenth Burton seized the Comanche and the Fannie Butler, which were carrying provisions for the enemy valued at $25,000. Word soon reached Texas that the Mexican Congress had repudiated Santa Anna, rejected his treaties, and ordered the war with Texas to continue.

There was a widespread clamor that Santa Anna should be put to death, and on June 4-after the dictator, his secretary Ramón Martínez Caro, and Col. Juan N. Almonte had been put aboard the Invincible to be returned to Veracruz-Gen. Thomas Jefferson Green, who had just arrived from the United States with volunteers, compelled President Burnet to remove the Mexicans from the vessel and confine them. On June 25 Burnet appointed as secretary of war Mirabeau B. Lamar, a major general, to succeed Rusk, who had asked to be relieved. But with word that Gen. José de Urrea was advancing on Goliad, Rusk changed his mind about retiring. Thomas Jefferson Green and Felix Huston, who had brought volunteers from Mississippi, stirred up the soldiers against Lamar, and Rusk resumed command. When Urrea failed to appear, Rusk vacated his command and the army chose Huston to replace him. Army unrest continued as the officers openly defied the government and threatened to impose a military dictatorship.

There were also other problems. On the morning of May 19, Comanche and Caddo Indians attacked Fort Parker, on the Navasota River some sixty miles above the settlements, and carried into captivity two women and three children. The government lacked the men and resources to retaliate. Communications were poor, roads were few, and there was no regular mail system. The treasury was empty, the new nation's credit was in low repute, money was scarce. There was much confusion over land titles. Many families were nearly destitute. They had lost heavily in the Runaway Scrape after the fall of the Alamo, and upon returning home found their property ravaged and their stock consumed or scattered. By July Burnet and his cabinet began shifting responsibilities. The ad interim president called an election for the first Monday in September to set up a government under the constitution. The voters were asked to (1) approve the constitution, (2) authorize Congress to amend the constitution, (3) elect a president, other officers, and members of Congress, and (4) express their views on annexation to the United States.

The choice of a president caused concern. Henry Smith, governor of the provisional government, quickly announced his candidacy for the office. Stephen F. Austin also entered the race, but he had accumulated enemies because of the land speculations of his business associate Samuel May Williams. Many newcomers to Texas knew little of Austin, and some thought he had been too slow in supporting the idea of independence. Rusk refused to run. Finally, just eleven days before the election, Sam Houston became an active candidate. On election day, September 5, Houston received 5,119 votes, Smith 743, and Austin 587. Lamar, the "keenest blade" at San Jacinto, was elected vice president. Houston received strong support from the army and from those who believed that his election would ensure internal stability and hasten recognition by world powers and early annexation to the United States. He was also expected to stand firm against Mexico and seek recognition of Texas independence. The people voted overwhelmingly to accept the constitution and to seek annexation, but they denied Congress the power of amendment.

The First Texas Congress assembled at Columbia on October 3, 1836. It consisted of fourteen senators and twenty-nine representatives. The next day ad interim President Burnet delivered a valedictory address. He urged Congress to authorize land grants to the veterans of the revolution and reminded his listeners that the national debt stood at $1,250,000. On October 22 Houston took the oath of office as president before a joint session of Congress. In his inaugural, he stressed the need for peace treaties with the Indians and for constant vigilance regarding "our national enemies-the Mexicans." He hoped to see Texas annexed to the United States. Houston requested the Senate to confirm his cabinet appointments. He named Stephen F. Austin to be secretary of state; Henry Smith, secretary of the treasury; Thomas J. Rusk and Samuel Rhoads Fisher secretary of war and secretary of the navy, respectively; and James Pinckney Henderson, attorney general. When Congress later established the office of postmaster general, Houston named Robert Barr of Nacogdoches to that post, and at Barr's death chose John Rice Jones, who had held the office under the provisional government, as his successor. Jones patterned the Texas postal system, which was placed in 1841 under the State Department, after that of the United States. All persons transporting mail for the Post Office Department during 1837 could take payment in land at fifty cents an acre and pay expenses. Postal rates were 6¼ cents for the first twenty miles, and rose to 12½ cents for up to fifty miles. The rates applied to one-page letters folded over and addressed on the front. Envelopes came into use around 1845.

Congress adopted a flag and a seal for the new republic. The first national flag had "an azure ground, with a large golden star central." In January of 1839, the flag was redesigned to have a blue perpendicular stripe one-third the its length, a white star with five points in the center of the blue field, and two horizontal stripes of equal width, the upper being white and the lower red. This "Lone Star Flag" remained the state flag after annexation. Provisional governor Smith had used a large overcoat button with a star for a seal. This design led Congress on December 10 to decree that the seal would be circular with a single star and the words "Republic of Texas" encircling it. In 1839 Congress decreed that the seal should include "a white star of five points, on an azure ground, encircled by an olive and live oak branches, and the letters Republic of Texas."

The court system inaugurated by Congress included a Supreme Court consisting of a chief justice appointed by the president and four associate justices, elected by a joint ballot of both houses of Congress for four-year terms and eligible for reelection. The associates also presided over four judicial districts. Houston nominated James Collinsworth to be the first chief justice. The county-court system consisted of a chief justice and two associates, chosen by a majority of the justices of the peace in the county. Each county was also to have a sheriff, a coroner, justices of the peace, and constables to serve two-year terms. Congress formed twenty-three counties, whose boundaries generally coincided with the existing municipalities.

The choice of a national capital proved difficult, and each house appointed a committee to make recommendations. The Senate selected Nacogdoches, while the lower house favored a site at San Jacinto. On November 14, the two houses agreed on a temporary location. Augustus Chapman Allen and John Kirby Allen, two brothers who were promoting a new town named Houston on Buffalo Bayou, offered to provide buildings for the government and lodgings for congressmen. Congress chose Houston to be the temporary capital, and the government moved there in April 1837.

On December 19, 1836, the Texas Congress unilaterally set the boundaries of the republic. It declared the Rio Grande to be the southern boundary, even though Mexico had refused to recognize Texas independence. The eastern border with Louisiana presented problems. Houston took up the matter with the United States through diplomatic channels, and a treaty was signed in Washington on April 25, 1838, which provided that each government would appoint a commissioner and a surveyor to run the boundary. Texas chose Memucan Hunt and John Overton to join their United States counterparts at the mouth of the Sabine River. The work stalled when the commissioners could not agree on whether Sabine Lakeqv was the "Sabine river" named in the treaty. On November 24, 1849, after annexation, the United States Congress recognized the Texas claim that the boundary ran through the middle of the lake.

National defense and frontier protection also claimed Houston's attention. Threats of a Mexican invasion and the fear of Indian raids kept the western counties in turmoil. Congress passed several acts dealing with frontier defense. In December 1836 it authorized a military force of 3,587 men and a battalion of 280 mounted riflemen, and appropriated funds to build forts and trading posts to encourage and supervise Indian trade. In case of a Mexican invasion, Congress empowered Houston to accept 40,000 volunteers from the United States. President Houston took a practical view of the situation. He downplayed Mexican threats, labeling them braggadocio and bombast. If the enemy invaded, he reasoned, Texans would rush to defend their homes. Ranger units on the frontier could handle the Indian situation. Houston's primary concern was to negotiate treaties with the Indians ensuring fair treatment. As for the army, Houston feared that Felix Huston, the commander and a military adventurer, might commit a rash act. He sent Albert Sidney Johnston to replace him. When Johnston reached Camp Independence, near Texana, on February 4, 1837, Huston challenged him to a duel and severely wounded him. Huston retained command, but later relinquished his position to Johnston. In May General Johnston left for New Orleans to seek medical attention and turned over his command to a Colonel Rodgers. The temporary commander urged the soldiers to march on the capital at Houston, "chastise the President" for his weak defense policies, "kick Congress out of doors, and give laws to Texas." At the same time Huston came to Houston and raised a clamor for a campaign against Mexico. When the general visited the president, Houston treated him cordially, but promptly ordered acting secretary of war William S. Fisher to furlough three of the four army regiments. The remaining troops were gradually disbanded. Houston planned to depend on the militia, ranger companies, and troops called for special duty.

Houston hoped, by keeping military units out of the Indian country and seeking treaties with various tribes, to avoid difficulties with the Indians. He sent friendly "talks" to the Shawnees, Cherokees, Alabama-Coushattas, Lipans, Tehuacanas, Tonkawas, Comanches, Kichais, and other groups. The most pressing problem involved the Cherokees, who had settled on rich lands along the Sabine and elsewhere in East Texas. Neither Spain nor Mexico had given them title to their lands. At the time of the Texas Revolution, the Consultation, hoping to keep the Cherokees and their associated bands quiet, sent Sam Houston to make a treaty guaranteeing them title to their land, and they had remained quiet during the difficult days. When Houston became president, he submitted the Cherokee treaty to the Senate for ratification, but that body killed it in December 1837. In October 1838 Houston authorized agents to run a line between the settlements and the properties of the Cherokees and associate bands, per the treaty of 1836, but he had to halt the project when difficulties developed.

Land disposal presented another problem that Houston grappled. In 1836 the Republic of Texas had a public domain of 251,579,800 acres (minus 26,280,000 acres granted before the revolution). This land eventually freed Texas from debt, pay for military services and public buildings, and provided endowments for many of her institutions. The Texas Congress had voted liberal land laws in 1836. Under the constitution, the heads of families (blacks and Indians excepted) living in Texas on March 2, 1836, could apply for a square league (4,428 acres) and a labor (177.1 acres) of land. Single men over age seventeen could receive one-third of a league. No one was required to live on the land. To encourage settlement, Congress also offered immigrants arriving between March 2, 1836, and October 1, 1837, a grant of 1,280 acres for heads of families and 640 acres for single men. Congress later allowed 640 acres and 320 acres, respectively, to heads of family and single men arriving after October 1, 1837, and before January 1, 1842. However, all immigrants arriving after March 2, 1836, had to live in Texas three years to receive clear title. Texas Revolution veterans arriving before August 1, 1836, received the same grants as original colonists and if permanently disabled could claim an additional 640 acres (known as donation grants). Veterans of the battle of San Jacinto (including those wounded on April 20 before the battle and members of the baggage and camp guard), participants in the siege of Bexar, and the heirs and survivors of those who died at the Alamo or had served in the Matamoros and Goliad campaigns could receive additional land. Grants were given for postrevolution military service varying from 320 acres for three months' duty to 1,240 acres for twelve months'.

Land sales, however, ran into problems. Texas offered land scrip or land at fifty cents an acre, when public land in the United States was $1.25 an acre, but the republic actually made few sales. Scrip sales ran into the problems of depreciated currency and forged certificates. Despite the cheap selling price, land acquisition could be costly, since applicants had to pay for locating, surveying, and obtaining title, services that amounted to about one-third the value of the land. Because old settlers and veterans were not required to live upon the land to obtain title, they frequently sold their certificates to others who located land outside the settlements. This land often sat ten or more years before it became part of a county. To encourage home ownership Congress enacted a homestead law on January 26, 1839. The act, patterned somewhat after legislation of Coahuila and Texas, guaranteed every citizen or head of family in the republic "fifty acres of land or one town lot, including his or her homestead, and improvements not exceeding five hundred dollars in value." Earlier, in December 1836, Congress had voted to reopen the land offices closed by the Permanent Council and the Consultation. Houston vetoed the bill, saying that existing land claims should be validated before new surveys were made. Congress passed the law over his veto, but in December 1837, before it went into effect, the succeeding Congress enacted a more comprehensive land act. It called for opening a land office for the use of old settlers and soldiers in February 1838, and for all others six months later. Houston vetoed the bill, but saw it passed over his veto. As Congress refused to modify the land laws, Houston kept the General Land Office closed throughout his administration.

Meeting in special session in May 1837 in Houston, the First Congress instituted a commission-at-large to locate a permanent capital. The commission recommended Bastrop (first choice), Washington-on-the Brazos, San Felipe, and Gonzales. As no action was taken, in December Congress selected a site commission from its members, and in April 1838, the group picked a vacant tract on the Colorado near La Grange. In January 1839 under the Lamar administration, Congress authorized still a third commission, drawn from its membership. It stipulated that the site be between the Trinity and Colorado rivers and north of the Old San Antonio Road and recommended that the capital be named Austin. The commissioners selected the frontier settlement of Waterloo, on the east bank of the Colorado some thirty-five miles above Bastrop, and purchased 7,135 acres of land there for $21,000. The site was surveyed into city lots, and construction began on government buildings, hotels, business houses, and homes. The Texas government moved to Austin in October 1839.

Two days after the constitutional convention adjourned in March 1836, President Burnet had sent George Childress and Robert Hamilton, probably the wealthiest man in Texas to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence, to Washington to seek recognition of the new republic. These two men joined the three agents (Austin, Archer, and Wharton) already there. Childress and Hamilton met with Secretary of State John Forsyth, but they carried no official documents to prove that Texas had a de facto government, and he refused to negotiate. In May Burnet recalled all the agents and appointed James Collinsworth, who had been Burnet's secretary of state from April 29 to May 23, and Peter W. Grayson, the attorney general, to replace them. They were instructed to ask the United States to mediate to end the hostilities between Texas and Mexico and obtain recognition of Texas independence. They also were to stress the republic's interest in annexation. During the summer of 1836 President Jackson sent Henry M. Morfit, a State Department clerk, as a special agent to Texas to collect information on the republic's population, strength, and ability to maintain independence. In August, Morfit filed his report. He estimated the population at 30,000 Anglo-Americans, 3,478 Tejanos, 14,200 Indians, of which 8,000 belonged to civilized tribes that had migrated from the United States, and a slave population of 5,000, plus a few free blacks. The population was small, Texas independence was far from secure, the government had a heavy debt, and there was a vast tract of contested vacant land between the settlements and the Rio Grande. Morfit advised the United States to delay recognition. In his annual message to Congress on December 21, 1836, Jackson cited Morfit's report and stated that the United States traditionally had accorded recognition only when a new community could maintain its independence. Texas was threatened by "an immense disparity of physical force on the side of Mexico," which might recover its lost dominion. Jackson left the disposition of the matter to Congress.

In the meantime, Houston, recently elected president of Texas, recalled Grayson and Collinsworth and dispatched William H. Wharton to Washington with instructions to seek recognition on both de jure and de facto grounds. If Wharton succeeded he would present his credentials as minister. Memucan Hunt soon joined him. They reported that Powhatan Ellis, United States minister to Mexico, had arrived in Washington and stated that Mexico was filled with anarchy, revolution, and bankruptcy. It would be impossible for her to invade Texas. France, Great Britain, and the United States were clamoring for the payment of claims of their citizens against Mexico. On March 1, 1837, the United States Congress, receiving memorials and petitions demanding the recognition of Texas independence, passed a resolution to provide money for "a diplomatic agent" to Texas. Jackson signed the resolution and appointed Alcée Louis La Branche of Louisiana to be chargé d'affaires to the Republic of Texas. The United States Congress adjourned on July 9, 1838, without acting upon the question of annexation. Houston replaced Hunt with Anson Jones, a member of the Texas Congress. Jones had introduced a resolution urging Houston to withdraw the offer of annexation, saying that Texas had grown in strength and resources and no longer needed ties with the United States. In Washington on October 12, 1838, Jones informed Secretary Forsyth that Texas had withdrawn its request for annexation. The issue lay dormant for several years.

In the fall of 1838 Houston sent James Pinckney Henderson abroad to seek recognition of Texas by England and France. The withdrawal of the annexation proposal in Washington helped facilitate his mission. France, being at war with Mexico, signed a treaty on September 25, 1839, recognizing Texas independence. England, in spite of slavery in the young republic and her desire to see the abolition of slavery worldwide, could not stand idly by and see France gain influence and trade privileges in Texas. Also, England had just settled the Maine boundary issue with the United States but faced hostilities over her claims in Oregon and the controversial Pacific Northwest boundary. She needed a supply of cotton if war came. In the fall of 1840, Lord Aberdeen announced that Her Majesty's government would recognize Texas independence, and on November 13-16, three treaties were signed that dealt with independence, commerce and navigation, and suppression of the African slave trade. A month earlier, on September 18, Texas had concluded a treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation with the Netherlands. The three treaties with England were not ratified until December 1841, soon after Houston's election for a second term to the Texas presidency. Houston named Ashbel Smith minister to Great Britain and France and sent James Reily to represent Texas in Washington, D.C. He instructed both men to get the three nations to exert pressure on Mexico for peace and recognition.

During Houston's first administration (1836-38), the public debt of the republic soared from approximately $1,250,000 to $3,250,000. Houston's successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, pursued aggressive policies toward Mexico and the Indians that added $4,855,000. In his second administration (1841-44) Houston and Congress pursued a policy of retrenchment and economy. The president abolished a number of offices in the government and in the army, combined or downgraded others, and cut salaries. Congress repealed the $5 million loan authorization voted earlier, as Texas had been unable to obtain money in the United States or Europe, and even reduced the pay of its own members. However, the Congress had overlooked an 1839 act that authorized the president to seek a loan of $1 million, and in June 1842, when he was considering a campaign against Mexico, Houston arranged to borrow that amount from Alexandre Bourgeois d'Orvanne of New Orleans. Congress also suspended payments on the public debt until the republic could meet its operating expenses. In his second term, Houston spent $511,000, only $100,000 of which went to Indian affairs. Though income slowly began to equal expenditures, at the time of annexation the public debt had risen to about $12 million.

Although Texas had no incorporated or private bank during the days of the republic, an effort was made to form a monstrous banking institution. The first Congress granted a ninety-eight-year charter to the Texas Railroad, Navigation, and Banking Company, whose sponsors included a number of prominent Texans. The company could capitalize at $5 million, enjoy extensive banking privileges, and offer loans to build canals and railroads to connect the Rio Grande and Sabine River. Opposition to the company developed when Branch T. Archer, a sponsor, tried to pay into the Texas treasury in discounted paper money the $25,000 required in gold and silver to launch the bank. The bank became the first political issue in the Houston administration. The constitution empowered Congress to coin money and decreed that gold and silver coins would be lawful tender with the same value as in the United States. The republic, however, never minted any coins.

Texas met her expenses in various ways. Officials sold confiscated and captured Mexican property and sought funds among well-wishers in the United States and elsewhere. The Bank of the United States in Philadelphia loaned the republic $457,380. Texas also sold land scrip in the United States for fifty cents an acre. As scrip sales were disappointing, Congress approved the issuance of paper money and, on June 9, 1837, authorized $500,000 in promissory notes bearing 10 percent interest and redeemable in twelve months. The notes began circulating on November 1. For note redemption, Congress pledged one-fourth of the proceeds from the sale of Matagorda and Galveston islands, a half million acres of public domain, all forfeited lands, and the faith of the republic. The notes were not to be reissued at maturity and depreciated very little. A replacement issue, called "engraved interest notes," declined in value from sixty-five cents on the dollar in May 1838 to forty cents by January 1839. The total face value of notes placed in circulation in 1837-38 was $1,165,139. The treasury also accepted audited government drafts. The Texas Congress approved "change notes" (treasury notes) up to $10,000 and specified that customs duties be paid in specie or treasury notes. As imports exceeded exports, gold and silver quickly drained from the republic. During the Lamar administration (1838-41), to curtail smuggling and increase tariff collection, Congress lowered rates nearly to a free-trade basis, but saw no positive effect. Direct taxes and license fees could be paid in depreciated currency until February 1842. On January 19, 1839, Congress approved non-interest-bearing promissory notes, called "red-backs." The treasury issued $2,780,361 in red-backs, valued at 37½ cents on the dollar in specie; these were worthless within three years. United States notes also circulated in Texas. Lamar appointed James Hamilton, a banker and former governor of South Carolina, to negotiate the authorized $5 million loan in either Europe or the United States, but Hamilton's attempts proved fruitless.

After the defeat at San Jacinto, Mexico sought to stir up discontent in Texas. Military commanders knew that there were restless groups around Nacogdoches and among various Indian tribes, and sent agents to East Texas to promote dissension. In the late summer of 1838, a rebellion flared near Nacogdoches. Vicente Córdova, a prominent citizen, organized a Mexican-Indian combination and disclaimed allegiance to Texas. Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Rusk, the local militia commander, called for volunteers. Córdova boldly attacked Rusk's camp on September 16, but was repulsed. In early March of 1839, with fifty-three Mexicans, a few Indians, and six blacks, Córdova sought to travel from the upper Trinity along the frontier to Matamoros. Near Austin, scouts discovered his trail, and Col. Edward Burleson at Bastrop gathered eighty men and broke up the Córdova party on Mill Creek near the Guadalupe River. In May, Manuel Flores, a Mexican agent, left Matamoros to contact Córdova, unaware of his flight. Texas Rangersqv intercepted Flores's party near Onion Creek, killed the emissary, and dispersed his men.

Upon taking office in December 1838, Lamar was convinced that the Cherokees were in treasonable correspondence with the Mexicans, and launched a campaign that drove them from Texas. Soldiers also forced the Shawnees, Alabamas, and Coushattas to abandon their hunting grounds; the last two tribes were given lands in East Texas. Speculators and settlers swarmed into vacated Indian land. Lamar also wanted to end Comanche depredations on the frontier. In 1839 ranger parties based in San Antonio invaded Comanche country and fought several engagements. Aware of the Cherokee expulsion, the Comanches sent a small delegation to San Antonio to talk peace. Texas authorities agreed to negotiate if the Indians brought in their white captives. On March 19, 1840, sixty-five Comanches showed up with one white prisoner, a twelve-year old girl by the name of Matilda Lockhart. Matilda said the Comanches had other prisoners. The Texans demanded the remaining prisoners and tried to hold the Indians as hostages. In what became known as the Council House Fight, thirty-five Indians and seven Texans were killed. Furious over the massacre, the Comanches killed their captives and descended several hundred strong on San Antonio but were unable to coax a fight and therefore rode away. Beginning in July the Comanches hit the frontier counties in force, with some 1,000 warriors descending the Guadalupe valley toward the coast. At Plum Creek, near the site of present Lockhart, Capt. Mathew Caldwell, Col. Edward Burleson, and General Felix Huston combined their forces and scattered the marauders (see PLUM CREEK, BATTLE OF). In October Col. John H. Mooreqv attacked Comanche camps west of the settlement line. Near the site of present-day Colorado City, his force surprised and killed more than 130 Indians.

In his second term as president, Sam Houston continued to negotiate with the Indian tribes and sought to rescue white captives. His policy of conciliation proved successful and was far less expensive than Lamar's policy. In August 1842, Houston tried to contact the Apaches and other tribes in Northwest Texas, and in October he met the Lipan Apaches and Tonkawas at the Waco village (see WICHITA INDIANS) on the Brazos. The president wanted to establish trading houses on the Brazos, believing that these establishments, lying west of the settlements, would provide protection. Coffee's Station, opened in 1837 on the Red River on a north-south Indian trail, had been successful. John F. Torrey started posts at Austin, San Antonio, and New Braunfels and near Waco. Houston became a stockholder in the Torrey trading houses. On September 29, 1843, Edward H. Tarrant and George W. Terrell concluded a treaty with nine Indian tribes at Bird's Fort near the site of present Arlington. The Senate ratified the treaty, but the government made no demarcation line between white and Indian territory. The largest Indian council held in the republic met in October 1844 near Waco, where a treaty was concluded with the Waco, Tawakoni, Kichai, and Wichita Indians.

Presidents of the republic could not succeed themselves. Toward the end of Houston's first term as president, which ended on December 10, 1838, Lamar announced his candidacy. Houston supporters tried to get Rusk to run, but he refused. Also Rusk lacked two months meeting the constitutional age requirement. Houston supporters next endorsed Peter W. Grayson, the attorney general, who had worked in Washington, but on his way back to Texas Grayson committed suicide at Bean's Station in eastern Tennessee. The Houstonites then approached Chief Justice James Collinsworth, but in late July he fell overboard in Galveston Bay and drowned. Lamar campaigned vigorously, promised to remedy the mistakes of the Houston administration, and won by a vote of 6,995 to 252 over Senator Robert Wilson, who represented Liberty and Harrisburg (later Harris) counties. David Burnet, the former ad interim president, was elected vice president. At the Lamar inaugural in Houston on December 10, Houston appeared in colonial costume and powdered wig and gave a three-hour "Farewell Address." Algernon P. Thompson, Lamar's secretary, reported that the new president was indisposed and read his inaugural remarks. Lamar picked Barnard E. Bee to be secretary of state, retained Robert Barr as postmaster general, asked Albert Sidney Johnston to be secretary of war, and made Memucan Hunt secretary of the navy. Richard G. Dunlap and John C. Watrous were appointed secretary of the treasury and attorney general, respectively.

In his message to the Texas Congress on December 21, President Lamar spoke against annexation. He saw no value in a tie with the United States, and predicted that Texas could someday become a great nation extending to the Pacific. Lamar called for far-reaching public programs. He recommended the establishment of a national bank, owned and operated by the government, and urged the establishment of public free schools and the founding of a university. He wanted the municipal code reformed to coordinate Mexican and United States law in the republic. He also wanted increased protection for the western frontier. He declared that neither the native nor the immigrant tribes had a cause of complaint and denied that the Cherokees or others had legal claims to land. Lamar recommended the building of military posts along the frontier, and the formation of a permanent military force capable of protecting the nation's borders. He promised to prosecute the war against Mexico until Mexico recognized Texas independence. He stated that Texas needed a navy to protect its commerce on the high seas and urged legislation to reserve all minerals for government use as well as a program to turn them to the advantage of the nation. Lamar favored continuing the tariff, but hoped some day to see Texas ports free and open. Congress responded to his message by authorizing a force of fifteen companies to be stationed in military colonies at eight places on the frontier. These were to be located on the Red River, at the Three Forks of the Trinity, on the Brazos, on the Colorado River, on the Saint Marks (San Marcos) River, near the headwaters of Cibolo Creek, on the Frio River, and on the Nueces. At each site, three leagues of land was to be surveyed into 160-acre tracts, and each soldier who fulfilled his enlistment would receive a tract. Bona fide settlers who lived on the land for three years also would be given tracts. In addition, the government planned to build sixteen trading posts near the settlement line. On January 1, 1839, the Texas Congress authorized Lamar to enroll eight companies of mounted volunteers for six months' service and appropriated $75,000 to sustain the force. Congress also set aside $5,000 to recruit and maintain a company of fifty-six rangers to patrol western Gonzales County for three months and three mounted companies for immediate service against the hostile Indians in Bastrop, Milam, and Robertson counties. An additional two companies were to protect San Patricio, Goliad, and Refugio counties. Congress appropriated a million dollars in promissory notes to cover the expenses for these units.

At the beginning of the Lamar administration Mexico was temporarily distracted. Because of unresolved French claims the French Navy had blockaded the Mexican coast and shelled and captured Veracruz. The Centralist Mexican government also faced a revolt by Federalists in its northern states. Tension increased when Lamar threatened to launch an offensive against Mexico if that nation refused to recognize Texas independence. Texan military units under colonels Reuben Ross, Juan N. Seguin and William S. Fisher crossed the Rio Grande and joined the Mexican Federalists, ignoring Lamar's call to return. In February 1839 Lamar increased the pressure on Mexico. He appointed Secretary of State Bee minister extraordinary and plenipotentiary to Mexico to request recognition of Texas independence and to conclude a treaty of peace, amity, and commerce. Bee also was to seek an agreement fixing the national boundary at the Rio Grande from its mouth to its source. If Mexico refused these requests, Bee could offer $5 million for the territory that Texas claimed by the act of December 19, 1836, territory that lay outside the bounds recognized by Mexican law. When Bee reached Veracruz, the French had withdrawn and the Centralists were strengthening their position. However, Juan Vitalba, a secret agent of Santa Anna who was serving temporarily as president, made overtures and hinted at possible negotiations. Lamar asked James Treat, a former resident of Mexico who knew Santa Anna and other Mexican leaders, to act as a confidential agent and attempt negotiations. Treat reached Veracruz on November 28, 1839, when the Federalists and their Texan allies were at the gates of Matamoros. The alliance blocked his plans. A year later, in September 1840, Treat proposed to the Mexican minister of foreign affairs an extended armistice but was ignored.

A Mexican invasion of Texas was now rumored. Gen. Felix Huston proposed sending an expedition of 1,000 men into Chihuahua, believing the move would eventually force any Mexican army that crossed the Rio Grande downstream to withdraw. Congress did not act, however, and in March 1841 Lamar appointed James Webb, former attorney general, to replace Bee as secretary of state and sent him to Mexico. Webb was denied permission to land at Veracruz. On June 29, the president recommended that Texas recognize the independence of Yucatán and Tabasco and join in a declaration of war against Mexico. Lamar also urged attention to the upper part of the Rio Grande. The Fifth Congress debated bills but refused to finance an expedition to establish Texas authority over its far-western claims. Congress also failed to appropriate money to maintain the army, and Lamar disbanded the military on March 24, 1841.

In November, with a large amount of military equipment on hand, the president urged Congress to authorize an expedition to Santa Fe. Lamar believed that the New Mexicans were restless under Governor Manuel Armijo. In April 1840 he had addressed a letter to the citizens of Santa Fe, saying that the United States and France had recognized Texas independence, and that he hoped to send commissioners to explain his concern for their wellbeing. When Santa Fe did not respond, Lamar was determined to send an expedition. He believed that Texas must extend its authority over its western claims, divert a part of the Santa Fe -St. Louis trade through its ports, and encourage the 80,000 inhabitants of New Mexico to sever their ties with Mexico and turn to Texas. If the United States took over New Mexico, however, it would extend its influence to the Pacific and complicate the Texas claims. On June 20, 1841, a large caravan, officially designated the Santa Fe Pioneers, left the Austin vicinity. Dr. Richard F. Brenham, William G. Cooke, and José Antonio Navarro traveled along as commissioners to treat with the inhabitants of New Mexico. Gen. Hugh McLeod commanded a military escort of 270 men. The civilian component included fifty-one persons, principally merchants, traders, and teamsters, with twenty-one wagons. After crossing the vast plains of West Texas under great hardship, on September 17 the expedition reached the village of Anton Chico, east of Santa Fe. There they met Armijo's forces and surrendered. The Mexicans marched the prisoners to Mexico City and held them until the following April.

The Lamar administration was drawing to an end. When the Sixth Congress assembled in Austin on November 1, 1841, the Rio Grande frontier was the scene of constant attacks by Texas renegades and Mexican outlaws and the nation was heavily in debt. Texans were in low spirits, the economy was depressed, and some families even considered moving back to the United States. During these years Texas regarded its vast public domain as critical to attracting settlers and encouraging economic development. On January 1, 1840, Congress passed a law permitting the president to issue colonization contracts to individuals or groups who would introduce a specified number of families within three years. A year later, Congress discussed a bill to allow the Franco-Texian Commercial and Colonization Company (also called the Franco-Texienne Company) to bring in 8,000 families and build twenty forts from the Red River to the Rio Grande. The settlers would be exempted from all taxes and tariffs for twenty years. The company would receive three million acres of land divided into sixteen tracts and have trading privileges with the New Mexican settlements. The bill passed the House but died in the Senate. Lamar approved a number of colonization contracts, however. On August 30, 1841, he authorized William S. Peters and his associates to settle 600 families from the Ohio valley and northeastern states on the northern frontier south of the Red River. Heads of families would each receive 640 acres of land and single men 320 acres. The settler would received title to half his land, while the contractor would hold the rest to pay for surveying, securing titles, furnishing seed, powder and shot, and providing a cabin. Other grants were made. On February 9, 1842, William Kennedy, an Englishman, with William Pringle, the Frenchman Henri Castro, and others each received permission to settle 600 or more immigrants between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. Castro sent out 300 colonists, principally from Alsace, to settle on the Medina River at Castroville. By 1845 he had introduced a total of 2,134 settlers. Kennedy and his associates planned to place families south of the Nueces River, but the colony never materialized.

During his second administration, Houston continued the settlement program. To strengthen frontier defense, he signed a contract on June 7, 1842 with Alexandre Bourgeois d'Orvanne and Armand Ducos to settle 600 French families on the headwaters of the Medina and Frio rivers and 500 families along the lower Rio Grande. Two Germans, Henry F. Fisher and Burchard Miller, contracted to locate 1,000 families of Germans, Swiss, Danes, Swedes, Norwegians, and Dutch immigrants between the Llano and Colorado rivers. The grant covered about three million acres, but the contractors introduced very few settlers. The Adelsverein, or Association of Noblemen, was one of the most successful colonizing enterprises. Twenty-five German noblemen organized a company at Biebrich am Rhein in April 1842, and sent agents to Texas to confer with President Houston, but they failed to obtain a grant. On March 22, 1844, the association acquired a large tract west of San Antonio from Bourgeois d'Orvanne and sent Prince Carl of Solms-Braunfels as commissioner general to Texas. Informed that the Bourgeois grant had been forfeited, Solms purchased the Fisher-Miller Land Grant, 3,878,000 acres that ran along the Colorado River and west to the Llano River. Solms also obtained a tract at the junction of Cibolo Creek and the San Antonio River. To establish a station halfway to the Fisher-Miller grant, he bought the so-called Comal Tract and founded the town of New Braunfels. In 1846 John O. Meusebach, who succeeded Solms-Braunfels as agent, founded Fredericksburg on the Pedernales River. Although after five years the Adelsverein went bankrupt, it had brought 7,380 immigrants to Texas. Charles Fenton Mercer, an agent of the Peters colony, contracted in January 1844 to settle 100 families within five years on any unappropriated lands in the republic. A number of families came in, but controversy and lawsuits plagued both the contractor and the settlers from the beginning and into the 1930s.

During the period of the republic, the population of Texas increased about 7,000 per year, primarily from immigration. By 1847 the white population, including Mexican immigrants, had risen to 102,961, and the number of slaves to 38,753. The growth was due largely to liberal land policies and expanding opportunities. Like other frontier areas, Texas acquired a reputation as a land of sharp dealers, lawlessness, rowdiness, and fraudulence. Land frauds were numerous and law enforcement agencies were weak or nonexistent, but Texans developed an ability to handle challenges. They elected few demagogues to office and were remarkably fortunate in their choice of leaders.

Early in his administration, Lamar promoted public education. On January 26, 1839, Congress set aside three square leagues of land in each county to support primary schools or academies. It also assigned fifty leagues of land for two universities. The next year the county allotment was increased to four leagues, and teachers were required to provide certificates indicating they could teach the basic courses. The republic, however, failed to establish a public school system or to found a university. Private and denominational schools filled the void. The first Protestant church-related school was Rutersville University, near La Grange, opened in January 1840 by Methodists. Congress provided a charter and four leagues of land. The school had preparatory and female departments, and added college work for men. During the republic, Rutersville was the foremost college in Texas. In 1842 the University of San Augustine, at San Augustine in East Texas, opened with a grammar school and female and collegiate departments. It prided itself on its laboratory work in science. McKenzie College, started near Clarksville in 1841, at one time had more than 300 boarding students. Marshall University, a coeducational institution, received its charter in 1842. Its female department eventually became a separate institution. Nacogdoches University, probably the first nonsectarian institution of higher learning in Texas, chartered on February 3, 1845, had an endowment of 29,712 acres of land and $2,699 in personal property. That same month Baylor University was opened near Independence.

In the fall of 1841 Houston and Burnet were candidates for president. Campaign issues included the Franco-Texian Bill, promoted by Houston; Houston and Burnet's questionable role in making land grants; frontier protection; making Houston the capital; instituting reforms to ensure land titles; retrenchment; and the redemption of the nation's honor, desecrated by Mexico. Houston was pictured as representing eastern Texas (except Nacogdoches County, where the Cherokee land question made Burnet the favorite), while Burnet was the champion of the western counties. On September 6 Houston easily won a second term, and Burleson beat Hunt for vice president.

In his second administration, Houston reversed many of Lamar's policies. He sought peace treaties with the Indians, took a defensive stand against Mexico, and encouraged trade along the southern and western borders. Houston was vitally concerned with the location of the capital. Austin was on the frontier, far from the center of population. If Indian or Mexican intruders captured and burned the capital, the prestige of the government would suffer. Houston wanted the government returned to Houston, but the western counties protested and Congress balked. In early March 1842, when Gen. Rafael Vásquezqv crossed the Rio Grande with 700 soldiers and occupied San Antonio, Houston seized the opportunity to order removal of the national archives from Austin, but local citizens blocked the move. During the session of Congress called to discuss the Vásquez invasion, Houston brought up the moving of the capital, but had no success. In October he moved the government offices to Washington-on-the-Brazos. In late December, at the president's orders, Col. Thomas W. Ward, commissioner of the General Land Office, loaded the archives into wagons and sought to remove them to the new seat of government. Irate citizens overtook Ward at Kenney's Fort on Brushy Creek and retrieved the documents. The Texas seat of government remained at Washington-on-the-Brazos until July 1845.

Texas had two navies during its short history as a nation. The first was commanded by Charles E. Hawkins, who carried the title of commodore. To protect the supply line to New Orleans, on November 25, 1835, the General Council of the provisional government authorized the purchase of four schooners and granted letters of marque and reprisal to privateers until the ships were armed. The first navy included the 60-ton Liberty, the 125-ton Independence, the 125-ton Brutus, and the 125-ton Invincible. All four ships were lost by mid-1837. Early in 1838 Texas bought the merchant brig Potomac, but was unable to convert it to a man-of-war, and instead used it at the Galveston Navy Yard as a receiving vessel. In March 1839 the government converted the S.S. Charleston, a steam side-wheeler, into a man-of-war, rechristened it the Zavala, and sent it on a cruise to Yucatán. It ran aground in Galveston Bay in May 1842 and subsequently was sold for scrap.

Lamar established the second Texas navy. The fleet of six vessels included the schooners San Jacinto, San Antonio, and San Bernard, each 170 tons; the brigs Wharton and Archer, 400 tons each; and the sloop-of-war Austin, 600 tons. Commodore Edwin W. Moore made the Austin his flagship. In October 1840 the Texas Congress, lulled by an unofficial armistice, cut navy appropriations and tied up the fleet. The San Jacinto, mapping the Texas coast, was wrecked the same month. A year later, on September 18, 1841, Lamar agreed to participate in Yucatán's rebellion against Mexico and sent the navy to protect the Yucatán coast. Yucatán paid $8,000 a month to keep the fleet active. On becoming president again, Houston canceled Lamar's arrangements and ordered the fleet to sail home. The San Antonio reached Galveston on January 31, 1842, reported on Yucatecan matters, and went on to New Orleans for repairs. There the only mutiny in the Texas Navy occurred. United States authorities captured the mutineers, and Commodore Moore later court-martialed two of the men. In April Moore arrived in New Orleans and began haggling with Houston over repair bills. In February 1843, Moore learned that Yucatán would pay these bills and sailed for Campeche. Houston, who had been planning to sell the navy, declared Moore a pirate. The commodore settled his accounts with Yucatán and returned home. After trial by a court-martial, he was restored to command. Houston ordered the vessels decommissioned. At annexation, the Texas Navy was transferred to the United States Navy, which promptly sold all the vessels except the Austin. Other vessels of the Texas Navy had been abandoned in Galveston harbor, lost at sea, or wrecked by storm. The United States Navy refused to accept the Texas naval officers and canceled their commissions.

On October 9, 1841, Santa Anna reestablished himself as provisional president of Mexico and determined to renew hostilities against Texas. In early January of 1842, Gen. Mariano Arista, commanding the Army of the North, announced his intention of invading the "the Department of Texas." After Vásquez seized San Antonio in March, the western counties demanded a retaliatory strike at Mexico. Houston knew that such a campaign could not be sustained, but decided to let the agitators see for themselves. On March 17 he approved the undertaking and sent agents to the United States to recruit volunteers and obtain arms, munitions, and provisions. The soldiers, assembling under Gen. James Davis at Lipantitlán, on the Nueces near San Patricio, quickly became restless. Provisions were short, and gambling and drunkenness prevailed. Learning of the disorder, colonels Antonio Canales and Cayetano Montero camped on the Rio Grande near Mier and Camargo and launched a surprise attack on the Texan camp on July 7, but were beaten off. The Sixth Congress, meeting in special session, passed a "war bill," but Houston vetoed it as it appropriated no funds for the campaign. The army was disbanded.

The Mexican government was determined to keep the Texas frontier in turmoil. Santa Anna ordered Gen. Adrián Woll to attack San Antonio and informed the Mexican Congress that he planned to resubjugate Texas. Woll crossed the Rio Grande at Presidio del Río Grande (Eagle Pass), and made a surprise attack on San Antonio on the morning of September 11. The defenders, learning that the soldiers were Mexican regulars, surrendered. On the eighteenth Woll moved to Salado Creek, assaulted the Texans assembled on the creek east of San Antonio under Col. Mathew Caldwell, then withdrew to San Antonio. Mexican troops intercepted Capt. Nicholas M. Dawson and fifty-three volunteers from La Grange who tried to join Caldwell east of Salado Creek; the Mexicans killed thirty-six Texans and captured fifteen, of whom five were wounded. Two escaped from the battlefield. Woll sent fifty-two prisoners from San Antonio ahead to Mexico, evacuated San Antonio on the twentieth, and marched for the Rio Grande. Caldwell's forces and a small ranger party under Capt. John Coffee "Jack" Hays harassed the Mexicans as far as the Nueces River. After the battle of Salado Creek, Texans demanded retaliation and rushed to San Antonio as individuals, in companies, and in small groups. Houston sent Brig. Gen. Alexander Somervell to take charge of the force there. On November 25 Somervell headed for the border with more than 750 men and seized Laredo. Disgusted by the Texans' plundering, 187 men soon left for home. In December Somervell led the rest downriver, crossed the Rio Grande, and seized Guerrero. Unable to find provisions, he recrossed into Texas and ordered his men to prepare to return home. A large group, 309 men, broke off from the expedition and refused to return home. They organized under Col. William S. Fisher and marched down the east side of the Rio Grande, crossed the river opposite Mier, and demanded food and clothing from the inhabitants of Mier. A large body of Mexican troops was rushed to the town, and the Texans, facing odds of ten to one, surrendered on December 26. On their march to Mexico City, the prisoners overthrew their guards at Hacienda Salado, and sought to escape to Texas, but most of them were recaptured. Nicolás Bravo, the vice president, ordered that they be decimated. Seventeen drew black beans and were shot on March 25, 1843.

Like Lamar, Houston expressed concern over the western boundaries of Texas. In February 1843 his administration authorized Jacob Snively to raise a volunteer group to make a show of force in the northwest territory claimed by Texas. They hoped to prey on the Mexican caravans traveling that section of the Santa Fe Trail that crossed Texas territory. The men were to mount, arm, and equip themselves and share half the spoils; the other half would go to the republic. Earlier, in August 1842, Charles A. Warfield had received a similar commission, recruited a small party largely in Missouri, and briefly occupied the New Mexican town of Mora on the overland trail. Snively organized 175 men near Coffee's Station, on the Red River, and in April 1843 they rode north. From his camp about forty miles below where the Santa Fe Trail crossed the Arkansas River, Snively captured a New Mexican patrol guarding the trail. The ensuing foray was short-lived. Capt. Philip St. George Cooke, in command of United States dragoons escorting merchant caravans through Indian country, arrested and disarmed the Texans, allegedly for being on United States soil, and sent them home. The United States later paid for the arms they had taken from the Texans.

Internal disturbances also flared during Houston's second term. In Shelby County, Charles W. Jackson, a fugitive from Louisiana, ran for Congress and blamed his defeat on land sharks and counterfeiters of headright certificates. Joseph G. Goodbread, who headed the anti-Jackson faction, threatened to run him out of the country. In 1842 Jackson shot and killed Goodbread. At Jackson's trial, in Harrison County, the judge failed to appear on the second day and Jackson went free. He soon headed a force called the "Regulators," who sought to suppress crime in the area and harass Goodbread supporters. In response, Edward Merchant formed the "Moderators." In the spring of 1843 a civil war broke out between the factions in Shelby, Panola, and Harrison counties. Over the three following years more than fifty men were killed and numerous homes and other property were burnt or destroyed. Judge John M. Hansford was killed by the Regulators. In August 1844, President Houston called on both parties to lay down their arms and sent Travis G. Brooks and 600 militiamen to maintain order. They arrested leaders on both sides and took them to San Augustine, where Houston persuaded them to sign a peace agreement.

While in Perote Prison,qv James W. Robinson, a former acting governor of Texas during the Consultation, sought an interview with Santa Anna. He stated that if granted an audience, he could show how to arrange a lasting peace between Mexico and Texas. Santa Anna, being at war with Yucatán, agreed to hear Robinson. Under his proposals Texas would become an independent department (state) in the Mexican federation, be represented in the Mexican Congress, and be allowed to make its own laws. Texas would be granted amnesty for past acts against Mexico, and Mexico would station no troops in Texas. The Mexican president approved the proposals on February 18, 1843, and released Robinson to convey them to Texas. Houston studied the proposals and reasoned that Santa Anna's Yucatán problem might lead the Mexican president to agree to peace terms. Houston asked Charles Elliot, the British chargé d'affaires to Texas, to ask Richard Pakenham, the British minister in Mexico, to seek an armistice. Robinson wrote Santa Anna that Houston wanted an armistice of several months to give the people of Texas an opportunity to consider the proposals. When Santa Anna received Robinson's letter, he agreed to a truce. Houston proclaimed an armistice on June 15, 1843, and sent Samuel M. Williams and George W. Hockley as commissioners to meet their counterparts at Sabinas, near the Rio Grande. They were to arrange a general armistice and request that a commission meet in Mexico City to discuss a permanent peace. Houston was cautious and proclaimed martial law between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. Pakenham informed Houston that Santa Anna would release the Mier prisoners if the Texas president would release all Mexican prisoners. Houston ordered the prisoners released, but when no Mexicans arrived on the Rio Grande, Santa Anna canceled the exchange. The Texas and Mexican commissioners agreed on a permanent armistice on February 18, 1844, but Houston filed the document away without taking action because it referred to Texas as a Mexican department.

In the Texas presidential race of 1844, Vice President Edward Burleson faced Secretary of State Anson Jones, who had the support of Houston. Jones won by a large vote. After he was inaugurated on December 9, he launched a policy of economy, peaceful relations with the Indians, and a nonaggressive policy toward Mexico. As his administration also tackled the issue of annexation, Jones earned the sobriquet "Architect of Annexation." He, Houston, and their supporters knew that proper timing was essential in securing annexation. Upon taking office, Jones instructed Isaac Van Zandt, Texan chargé d'affaires to the United States, to decline all offers to negotiate an annexation treaty until it was known that the United States Senate definitely would ratify it. When President John Tyler reopened negotiations on annexation, Mexico became friendly to Texas. At the same time she threatened war with the United States if annexation were approved. In the United States, there was great sympathy for the Texas cause. The collapse of the Santa Fe expedition in 1841 and the Mexican invasions of 1842 had attracted widespread attention. In March 1842, Houston instructed James Reily, the Texas representative to Washington, to sound out the government on annexation. The United States, knowing the British wanted to mediate Texas-Mexican difficulties, saw a strong British influence looming in Texas affairs. President Tyler, a Whig with Southern views on slavery, had indicated in October that he wanted to open discussions leading to the annexation of Texas by treaty. An annexation treaty was completed on April 12, 1844, and signed by Secretary of State John C. Calhoun, Isaac Van Zandt, and Van Zandt's assistant, J. Pinckney Henderson.

Great Britain and France became concerned. The British Foreign Office, with French support, advised Ashbel Smith, the Texan agent to Great Britain and France, that a "diplomatic act" was needed to force Mexico to make peace with Texas and recognize its independence. They wanted the United States to join their efforts to end Texas-Mexican hostilities. Pakenham, however, opposed the plan, and the matter was dropped. Houston favored a "diplomatic act," but Anson Jones, the president elect, balked. Jones wanted annexation and thought that the threat of an alignment with England, connected with the cotton trade, was the key to achieving it. In June 1844 the United States Senate voted thirty-five to sixteen to reject the treaty.

The annexation of Texas also became a major issue in the United States election of 1844. The Democrats ran James K. Polk, of Tennessee, for president with the campaign slogan "the Re-Annexation of Texas and the Re-Occupation of Oregon," hoping to capture the expansionists' vote both North and South. The Democrats won by a large vote. Tyler viewed Polk's election as a mandate for immediate annexation. In his annual message on December 2, he urged Congress to approve annexation by a joint resolution, which Congress passed on February 28, 1845, and Tyler signed on March 1. He then dispatched Andrew Jackson Donelson, a nephew of Andrew Jackson, to Texas with instructions to press for its acceptance. The terms were generous. Texas would be annexed as a slave state rather than as a territory. She would keep her public lands and pay her own public debts. She could divide herself into as many as four additional states. The terms of annexation had to be accepted by January 1, 1846. In May 1845, the United States dispatched a fleet of warships to protect the Texas coast.

The British chargé d'affaires and the French minister asked President Jones to postpone action on the annexation agreement for ninety days because they wanted to arrange a settlement of matters between Mexico and Texas. Jones agreed to do so on March 29. The British and French emissaries reached Mexico City in mid-April. Luis G. Cuevas, minister of foreign relations, placed their proposals before the Mexican Congress, and in late April Mexico recognized Texas independence. The British minister handed a copy of the document to Jones on June 4, and he immediately announced a preliminary peace with Mexico. On the same day Jones signed a peace treaty with the last Comanche chief whose tribe had been at war with Texas, thus ending Indian hostilities for the republic.

Texas Enter the United States

President Jones issued a call on May 5 for a convention to be elected by the people to meet in Austin on July 4. At his call, the Texas Congress assembled on June 16 in special session at Washington-on-the-Brazos and rejected the Mexican offer for peace. They accepted the annexation agreement and approved elections for a convention. The convention met in Austin on July 4 and passed an ordinance to accept annexation. It then drafted the Constitution of 1845 and submitted both the annexation agreement and proposed constitution to a popular vote. On October 13 annexation was approved by a vote of 4,245 to 257, and the constitution by a vote of 4,174 to 312. The United States Congress approved the Texas state constitution, and Polk signed the act admitting Texas as a state on December 29, 1845. The fledgling republic, whose existence had spanned nine years, eleven months, and seventeen days, was no more. In a special election on December 15, Texans had elected officers for the new state government. The First Legislature convened in Austin on February 19, 1846. In a ceremony in front of the Capitol, President Jones gave a valedictory address, the flag of the republic was lowered, and the flag of the United States was raised above it. The ceremonies concluded with the inaugural address of the newly elected governor, J. Pinckney Henderson. By annexation Texas received the protection of a powerful country and the assurance of a bright future.

Texas Enters the Civil War

In 1859, most Texans cared little about secession. But several events swung the pendulum. Native American raids persisted on the frontier and Texas turned to the federal government. When Congress failed to offer aid, Texans lost faith in the government. About 90 percent of Texas' Anglo immigrants were from the South, and with the election of Abraham Lincoln as president, secessionists had more ammunition. On February 1st, 1861, exactly 25 years after Texas proclaimed independence from Mexico, the state seceded from the Union. The citizens of the State of Texas endorsed secession at the ballot box by a vote of 3-1.

Governor Houston was removed from office when he wouldn't support the action. Lt. Governor Edward Clark served out Houston's term. About 2,000 Texans volunteered to serve in the Union Army. More than 70,000 Texans served in the Confederate Army.

During the Civil War, "cotton roads" led from the Texas interior to the Mexican border towns along the Rio Grande. Haulers took bales down the hazardous roads through the brush South Texas country. Empty cotton wagons were then loaded with guns, ammunition, cloth, nails, sugar, medicine, and other supplies needed by Confederate troops in Texas.

The last battle of the Civil War was fought on Texas soil at Palmito Ranch east of Brownsville. About 300 Confederate soldiers led by Colonel John Solomon ford defeated Union forces that consisted of two African American regiments and a company of unmounted Texas cavalry. the battle took pace on may 12 -13, 1865, and the Confederates won. but they learned from Union prisoners that General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox more than a month earlier.

President Lincoln issued the emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and freed an estimated 200,000 slaves. But the news didn't reach Texas until June 19th, 1865, when Major General Gordon Granger read the proclamation in Galveston, June 19th, or "Juneteenth" became an anniversary to be remembered and honored by former slaves and Juneteenth celebrations spread across the state. The historic day drew official recognition when Texas State Representative Al Edwards of Houston sponsored House Bill 1016. On January 1, 1980, Juneteenth was made a state holiday, the first state holiday in the nation to honor emancipation.

Many German settlers in Central Texas preferred to remain neutral during the

Civil War. But Confederate military officials condemned them as traitors. When

Texan Partisan Rangers began lynching some of the men and boys, a few settlers

tried to flee to Mexico for safety. On August 10, 1862, the rangers caught up

with a group in Kinney County, near the Nueces River. The rangers attacked,