MEXICO'S COLONIAL ERA: The Settlement of New Spain

The fall of the Aztec Empire and capture of its ruler Cuauhtémoc (1521), left Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés in charge of a vast and largely unfamiliar land. By 1522 his sovereign, Carlos V, had bestowed upon him the title Governor and Captain General of Nueva España (New Spain). Cortés promptly founded the Ciudad de Mexico on the ruins of the once-majestic Tenochtitlán, building a European-style colonial capital with the rubble left from razed Aztec pyramids, temples and palaces.

Soon Cortés dispatched his lieutenants in every direction to explore and conquer more territory where they searched for gold and other riches, as well as possible routes for reaching Asia by sea. Cortés himself set off south towards Honduras on an expedition that would last nearly two years. In order to deter defiant Aztecs from rising up during his absence, he took Cuauhtémoc along as a hostage. But in the course of the perilous venture, in an apparent fit of paranoia, he ordered the last Aztec emperor to be tried and summarily hanged on grounds of treason.

Meanwhile, political intrigues were afoot among Cortés' enemies in both Spain and the colonies. In 1524 Carlos V had formed the Council of the Indies to administer its colonies in the western hemisphere. Three years later Nueva España's first Audiencia was appointed. In Spain the functions of these panels of oidores (judges) were limited to judicial matters, whereas in overseeing the colonies they wielded wide executive and legislative powers.

His absolute authority thus suspended, Cortés was ordered to return to Spain in the spring of 1528. Intent on securing the confidence of the Spanish King, he bore a host of new world riches as gifts for the monarch. These included not only gold and jade, but also exotic flora and fauna, ranging from cacao, a coveted Aztec delicacy, to brightly hued parrots, as well as a retinue of Indian nobles.

Cortés' tactics were at least partially successful. Denied the full command over New Spain that he desired, Cortés nonetheless returned to Mexico in 1530 with the title Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca. He retired to Cuernavaca to take charge of a vast estate, covering some 25,000 square miles, granted to him by the king. As his rivals continued to create troubles, Cortés sailed back to Spain, hoping to regain the King's good graces anew. Disillusioned at his failure to overcome growing alienation from the Crown, the great conquistador fell sick and died in 1547. A few years later his remains were returned to Mexico and laid to rest in the Niño Jesus Chapel near the Zócalo, Mexico City's main square.

Control of the first Audiencia had fallen into the hands of one of Cortés' most ardent enemies, the notorious Nuño de Guzmán. Ruthless and corrupt, he kept news of his dark deeds from reaching the Spanish Court by intercepting correspondence from his critics. When word did finally reach the King, he appointed a new Audiencia. to take over. Once Guzmán realized the tide was turning against him, he gathered a band of mercenaries and set off on an expedition to the western hinterlands. Cutting a bloody path of death and devastation wherever he went, Guzmán's violent rampage lasted several years before, under orders of the second Audiencia, he was arrested and sent back to Spain in irons.

Finally, in 1535, Antonio de Mendoza was appointed as the first of 61 viceroys who were to rule over Nueva España for the next three centuries. (see below) As the King's deputy, the Viceroy served as chief of all military, political and administrative officers. During Mendoza's 15-year rule the dimensions of colonial territories continued to grow, eventually expanding south to Honduras, north to what is now Kansas and as far east as today's New Orleans. Nueva España was divided into regions, many of which were designated with names from the homeland. Nueva Galicia was founded in 1548; Nueva Vizcaya in 1562; Nuevo León in 1579. Nuevo México was established in 1583. Spain's horizons were broadened even further as explorations along the Pacific coast led to the opening of maritime gateways to Asia. As far north as British Columbia, Canada, there are many spanish topographical place names.

The political system set up to run the country was modeled on that of Spain. Municipalities became the territorial unit of government. Largely self-governing, the Crown was represented by an alcalde mayor appointed by the Viceroy. These appointments contained one of the first seeds of popular discontent. With very few exceptions, only Spaniards, born in Spain, were given these positions. This policy was still in effect in 1810 at the start of the Mexican Revolution. Proclaiming his "Grito" on September 16th of that year, Father Miguel Hidalgo closed by shouting, "Death to the Gachupines. Literally translated as "spur wearers" it was the popular term describing Spaniards born in Spain.

Additionally, municipal freedom from central control came about because of difficulties of rapid communication with the central government in Mexico City. By 1571 there were 35 Spanish founded "royal" municipalities and by 1624, 82. As the population increased, Nueva España expanded. Nuevo Galicia now Jalisco, Nuevo Leon now Leon and finally Nuevo Mexico now Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico, became self-governing gobiernos largely unsupervised by the central government. This tradition of independence from central authority is still part of the Mexican scene. Governors of Mexican States routinely ignore or modify federal directives and presidentes ( mayors) of cities do the same with edicts from both state capitals and Mexico, D.F. Even the Mexican bureaucracy at times ignores the letter of the law.

The social system set up under the Colonial Government was, in the end, a major contributor to its failure since it froze the society, offering almost no chance of upward mobility. At the head of the pecking order were Spaniards born in Spain. Second but still well beneath them were the Criolles, people of pure Spanish blood born in the Colony. This group held secondary positions in the Government, Church and Army. Together with those born in Spain, they formed the elite group that ran the colony. Unions between Spaniards and indigenous people, almost always men with women, produced mestizos. By 1810 they were the majority of the population. Last in both social status and opportunity, were the Indians. Frozen into this rigid system, based on place of birth and bloodlines rather than ability, resentment between the various segments of society was inevitable. It was the Criolles who led the Mestizos in the revolution that broke the Spanish yoke.

Spain's interest in Nueva Espagna was almost totally economic. The welfare of the settlers was of little concern to the Crown. As long as a steady flow of silver, gold spices and tobacco enriched the royal coffers, local officials had almost complete independence. They competed for absolute power only with the Catholic Church. As time went by Government and Church built a power-sharing alliance that institutionalized the class system.

In the final analysis, the Colonial Government mirrored Spain. The concept of democracy was alien to the Spanish crown. This, too, is part of the legacy that produced the chaos after Independence was achieved. In the first 55 years of the Republic, 75 Presidents came and went. One of them, Santa Anna, served twelve times. It is only in the last 20 years that true democracy has started to emerge. Blaming this entirely on the Colonial Government is an over-simplification, but there is little doubt that many of the practices of the 300 years that it controlled the Colony, either knowingly or sub-consciously, still make up part of the Mexican Mystique.

Laws forbidding trade with any country other than Spain stifled chances for industrial development. The colony was regarded as simply a source of raw materials. Mining and agriculture, the principal source of raw materials, offered only menial, backbreaking jobs. Thus after the flood of Conversos who came to Nueva Espagna in the 1530's, seeking refuge from the Inquisition, migration to the Colony was a mere trickle. Territorial expansion led to the exploitation of natural riches, particularly gold, silver and other mineral resources. The yield from Mexico's mines doubled the world supply of silver in less than two centuries. With this new wealth colonial cities sprang up far and wide. Talented Indian stonemasons, who had once crafted temples and pyramids, were put to work building chapels, cathedrals, monasteries and convents, as well as administrative palaces and grand residences, for their new Spanish masters. The skill of those native hands remains visible in the 16th century structures that still grace Mexico today, from the nation's capital, to Queretaro, San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato, Morelia, Guadalajara, Zacatecas and the quintessential colonial city of Puebla.

Religion & Society in New Spain

No sooner had the Spanish conquistadores vanquished the Aztec Empire militarily, than the spiritual conquest of Indian Mexico began. The Spaniards were devoutly Roman Catholic. It should be remembered that Spain's rise to power came as a direct result of regaining the Iberian peninsula from Moslem rule. In return for having driven out the Moors, the Pope granted the Spanish Crown authority over the Church within its domain, effectively making the it an arm of the State. Thus, for Carlos V, the conquest of the Americas more than just a quest for territory and material riches. His personal mission as an agent of the Vatican was the ardent pursuit of souls for salvation.

At that time the Church's organization was divided into two distinct branches. Under the Papal grant of power to the Spanish Crown, the secular clergy was comprised of priests who served under their bishops. The missionary orders, on the other hand, were designated as self-governing bodies under the separate authority of their respective superiors, as decreed by Pope Leon X in 1521. Secular priests were prohibited from interfering with the regular clergy, on penalty of ex-communication. Thus, during Mexico's colonial era, the secular clergy worked hand in hand with civil authorities, while the missionary friars, laboring independently, tended to have greater influence over the common people.

The first Franciscan missionaries, sent by Carlos V at Cortés request, arrived in Mexico in 1523 and 1524. By 1559 there were 300 Franciscan friars at 80 missions throughout Nueva España. They were followed by the Dominicans (1525), the Augustinians (1533), and finally, the Jesuits (1571). Altogether some 12,000 churches were built during the three centuries of Spanish rule over Mexico.

Although their chief goal was to perform the sacraments and introduce the Indians to the fundamentals of Christian doctrine, in many respects the missionary friars laid the groundwork for the fusion of the Spanish and Mexican cultures. They won the trust of the native population by protecting them from the excesses to which many of the Spanish civilians were inclined. They also took responsibility for the basic education of the Indians, an effort greatly enhanced by their assiduous study of Indian languages. They established schools where youngsters learned to read and write and were introduced to European music and the arts. Adults were trained to practice agriculture and trades, learning European methods in masonry, carpentry, iron work, weaving, dying, and ceramics.

Many Catholic schools in Mexico today bear the name of Fray Pedro de Gante, the first of New Spain's distinguished missionary educators. The Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas, who rose to become Bishop of Chiapas, was nicknamed "Father of the Indians" for his staunch defense of the Indians' legal rights. Fray Toribio de Benavente, fondly dubbed Motolinía (meaning "poor one"), was a self-sacrificing man dedicated to protecting the natives. He penned a scholarly treatise entitled Historia de los Indios. Essential knowledge of Aztec life is largely attributed to Fray Bernardino de Sahagún for his richly detailed Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España.

The first archbishop of Mexico, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, was another steadfast advocate for the indigenous people who, in conjunction with Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, established the renowned Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco school for the sons of Indian nobles. He earned the moniker "Protector of the Indians" after founding of the Santa Fe hospices in Mexico City and Paztcuaro, where aid was dispensed to the poorest of natives. He also set up the first printing press in the Americas.

Since it was customary for Mesoamerican cultures to adopt the religion of conquering tribes, the Indians were not naturally inclined to resist conversion to Christianity. There were in fact certain similarities in doctrines and rituals that facilitated matters. Human sacrifice--a practice the Spaniards found particularly abhorrent--predisposed the Aztecs to readily accept the concept of consuming the body and blood of Christ in the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. Likewise, it was not a stretch for the Indians to substitute adoration of the Virgin Mary for worship of Tonantzin, their mother figure.

Although the church strove to put an end to most pagan practices, some ancient religious customs were assimilated in the celebration of Christians holidays. For example, All Souls Day, November 2nd, closely coincided with the Aztec's autumn rituals in honor of departed ancestors, giving rise to the unique Day of the Dead festivities still observed in Mexico today.

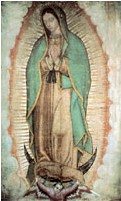

Perhaps the most

significant religious event of the Colonial period was the apparition of the

Virgin Mary (1531) to a newly converted

Indian baptized with the name Juan Diego. While walking across Tepeyac, a hill

located just north of the capital, he is said to have beheld a resplendent

vision of a dark-skinned woman. She entreated him to go to Bishop Zumárraga and

request that a temple be built in her honor on the sacred grounds where the

Aztecs had worshipped their mother goddess Tonantzin. As evidence of the

miraculous appearance, Juan Diego retrieved an armload of roses from the

normally barren hillside, gathering them up in his tilma (cotton cloak).

When he unleashed the cascade of flowers at the bishop's feet, he revealed a

stunning image of the Virgin imprinted on the cloak. Not unlike the Shroud of

Turin, the image of La Virgen de Guadalupe still defies scientific explanation.

La Guadalupana, Reina de Mexico (Queen of Mexico), has since become the

religious patroness of all Latin Americans.

Perhaps the most

significant religious event of the Colonial period was the apparition of the

Virgin Mary (1531) to a newly converted

Indian baptized with the name Juan Diego. While walking across Tepeyac, a hill

located just north of the capital, he is said to have beheld a resplendent

vision of a dark-skinned woman. She entreated him to go to Bishop Zumárraga and

request that a temple be built in her honor on the sacred grounds where the

Aztecs had worshipped their mother goddess Tonantzin. As evidence of the

miraculous appearance, Juan Diego retrieved an armload of roses from the

normally barren hillside, gathering them up in his tilma (cotton cloak).

When he unleashed the cascade of flowers at the bishop's feet, he revealed a

stunning image of the Virgin imprinted on the cloak. Not unlike the Shroud of

Turin, the image of La Virgen de Guadalupe still defies scientific explanation.

La Guadalupana, Reina de Mexico (Queen of Mexico), has since become the

religious patroness of all Latin Americans.

In the aftermath of the Conquest the Spaniards began to set up Nueva España's political, social and economic structure. While the Ciudad de Mexico was being erected on the ruins of the old Aztec capital, the remainder of the conquered territory was gradually divvied up into grants for huge estates, known as encomiendas, operated under a feudal system by some 500 Spanish landlords. Under the original scheme, title reverted to the Spanish Crown upon the death of the ecomendero (estate owner), but in time heirs were allowed retain rights by inheritance.

The encomendero was entitled to reap whatever benefit he could from the estate, including the unpaid labor of the native inhabitants for working the fields or mines. Theoretically, they were also obliged to look after the physical, intellectual and spiritual well-being of the Indians. With a few exceptions, most exploited their privileges without fulfilling their obligations. Communal village ownership of tillable lands--known as the ejido system--was also established during the early Colonial Period. All of these would become significant factors in subsequent events in Mexico's history.

In any case, although the encomienda system continued into the 18th century, its importance in the overall economy of New Spain was short-lived. The Spanish soldiers responsible for the conquest of Tenochtitlan--along with thousands of new Spanish adventurers who emigrated in the century following the Conquest--took little interest in working the land, preferring instead to set out northward in search of gold and other riches in the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola. The quest for this mythical land of plenty, probably invented by natives as a ploy to send earlier adventurers onward, ultimately proved fruitless.

As colonial society grew, a well-defined caste system developed. The top stratus was formed by Spaniards born in Spain, called peninsulares or gachupines, most of whom came from titled families and held the highest ranking posts in both the government and the clergy. Next came the criollos, those born in Mexico of Spanish parents. While few of the criollos who came to occupy official positions were able to rise above a secondary level, many others managed to prosper by becoming landowners and merchants . A growing number were able to enjoy lives of leisure thanks to the toil of Indians who turned their farms, ranches, mines and commercial ventures into productive enterprises.

The dearth of Spanish women at the start of the Colonial era led to numerous unions between Indian women and Spaniards. An immediate consequence was the birth of many mixed-blood--mostly illegitimate--offspring. These so-called mestizos made up a rapidly growing socioeconomic class that, for the most part, were considered inferior by pure-blood Spaniards. Mestizos --who today make up the vast majority of Mexico's population--were to remain poor and uneducated for many generations.

The native Indians were delegated to the next rung down New Spain's social ladder. Considered wards of the Crown and the Church, the law required that legal authorities, the clergy and the encomenderos protect their welfare. Nonetheless, the Spaniards depended heavily upon native labor. Scarcely looked upon as human beings, hundreds of thousands of Indians were literally worked to death. Others succumbed to new diseases introduced by the Spaniards: smallpox, measles, plague, tuberculosis, and even the common cold. At the time of the Conquest, about nine million indigenous people inhabited Mexico's central plateau. By 1600 they numbered a scant two and a half million.

The devastation of the Indian population created a significant labor shortage. This situation was remedied by importing thousands of African slaves. (Curiously, slavery of the Indians had been prohibited in the mid-16th century by Nueva España's second Viceroy, Luis de Velasco.) Although they came at a premium, due to high transportation costs, the Spaniards willingly paid for slaves who seemed to withstand both hard labor and harsh working conditions better than the Indians. With the remuneration received for their steadfast labor, many Blacks were eventually able to purchase their freedom.

Diverse racial subgroups originated in subsequent generations, including mulattos (Spanish-African), castizos (Spanish-Mestizo), zambos (Indian-African). Added to this mix were the large numbers of Filipinos, Chinese and Europeans of assorted nationalities who emigrated to Mexico during the era. Having emerged from this singular fusion, modern Mexican society has garnered the tag la raza cósmica--the cosmic race.

The Economy of New Spain

The chief function of the colonies in the eyes of the Spanish Hapsburg kings--who ruled until 1700--was to make Spain stronger, richer and more self-sufficient. Raw materials brought home from the New World were turned into finished goods, which were then exported to other European nations or sent back to the colonies to be sold for profit. Best of all, New Spain's wealth of silver and gold deposits could be tapped on to swell the royal coffers.

Although the economy of Nueva España was eventually transformed by the introduction of European crops, draft animals and technology, excessive controls stifled the initial growth of its industry and commerce. To secure its profits, the Crown held monopolies on products such as salt, gunpowder, mercury, pulque and tobacco. Economic activities deemed to compete with Spanish industry were severely restricted or prohibited altogether. The few industries that were permitted--tanning and weaving of coarse cloth, for example--were so tightly regulated that they were seldom profitable.

On the other hand, following the discovery of valuable mineral deposits Spain actively fostered the mining industry. Between 1546 and 1548 vast silver deposits were uncovered in Zacatecas, which swiftly grew to be the country's third largest city--surpassed only by the capital and Puebla. Booms later hit Guanajuato, San Luis Potosi, Pachuca and Taxco. By the early 17th Century, Zacatecas was producing a third of Mexico's silver and a fifth of the total world supply.

As early as 1536 copper, silver and cold coins were being milled in Mexico City at the Western Hemisphere's first mint. Silver coins in denominations of Ocho Reales were first struck in 1572. Better known as the Spanish Dollar, this hefty bit of change was widely circulated as legal tender throughout Europe and the Orient. The widespread practice of cutting the coin into smaller parts gave rise to the terms "pieces of eight" and "two bits." The dollar sign derives from the pillars of Hercules designed for some issues of the coin. By the end of the 18th Century Spanish dollars made up the bulk of England's treasury. Counter-marked with new seals, the coins were converted into official British currency.

Transporting New Spain's immense mineral wealth became something of a security nightmare. Masked bandits repeatedly ambushed mule trains bound for Mexico City, Acapulco or Veracruz. A greater threat were the English, French and Dutch pirates who prowled the Caribbean in search of Spanish galleons ripe for plunder.

Mining however was a secondary enterprise compared to agriculture. Indispensable to sustain a growing colonial society, farming and ranching quickly became New Spain's principal occupations. Cattle, sheep, and other livestock imported from Spain were driven north where ranchers settled across the open ranges near northern mining centers. Wheat, sugar cane, citrus and other fruits were introduced to more fertile lands. Again there were restrictions. Although wine and olive oil were staples of the Spanish diet, colonists were prohibited from planting vineyards and olive groves to protect the interests of farmers back in the homeland. The cultivation of mulberry bushes was also banned to safeguard to Spain's silk industry.

Initially, agricultural production was primarily geared for domestic consumption, but some of New Spain's unique products proved to have considerable export value. Cochineal and indigo dyes, derived from indigenous species, were in high demand for Europe's burgeoning textile industry. Cacao became an important cash crop once the Aztec delicacy xocoatl (chocolate) became all the rage in Continental society. Vanilla, sugar, henequén, cotton and tobacco also become lucrative crops as the demand for these products increased in markets abroad.

Considerable revenue was also generated through Spain's complex duty and tax system. All goods imported to the colonies were carried by Spanish ships manned by Spanish crews. The collection of duties was secured by channeling the annual voyage of the Spanish fleet to Veracruz. Similarly, the Manila Galleon, loaded with luxury goods from the Orient destined for Spain, disembarked once a year at Acapulco. The limited supply and high cost of essential imported merchandise spurred some enterprising colonists to begin producing substitutes. For example, locally-brewed beer became an increasingly popular beverage in lieu of expensive Spanish wines. In addition, the demand for contraband merchandise fomented a budding black market.

The economic picture began to change at the dawn of the 18th century when the Bourbon monarchs ascended the Spanish throne. Reforms in Spain's government and sweeping changes in its policies towards the colonies were instigated during the 1759-1788 reign of Charles III. Trade restrictions were greatly reduced. The Crown permitted New Spain to open new ports in Campeche and Yucatan and finally sanctioned free trade between other ports both in Spain and throughout the Americas.

Meanwhile, the Church had also begun to prosper. As most of the indigenous people had been Christianized during the first wave of mendicant friars, the clerics who arrived later took more interest in providing for the spiritual needs of wealthy Spanish settlers, many of whom in turn bequeathed their worldly goods to the Church. By the end of the 18th Century over half of New Spain's land and close to two thirds of the money in circulation had fallen into the hands of the Church.

By then Nueva España was the richest of all of Spain's overseas territories. Ten generations of colonists had enjoyed 300 hundred years of relative peace--a period that surpassed the duration of the Aztec Empire by a full century. But much of colonial society had tired of Spain's unrelenting extreme self-interest, as manifested by export controls and heavy taxation detrimental to internal economic development. The colony was well established and quite capable of self-government. At the same time political upheavals in Europe began to shake Spain. The philosophy behind the French and American revolutions spread to the Americas, acting as a catalyst for social and political unrest. Nueva España was now ripe for independence.

![]()

VICEROYS OF NEW SPAIN 1535-1821

BEFORE TREATY OF PARIS 1783

1535-1550 Antonio de Mendoza

1550-1564 Luis de Velasco (the elder)

1564-1566 Mexico governed by the Audiencia of New Spain

1566-1567 Gaston de Peralta, Marques de Falces

1568-1580 Martin Enriquez de Almanza

1580-1583 Lorenzo Suarez de Mendoza, Conde de Coruna

1584-1585 Pedro Moya y de Contreras, Arzobispo de Mexico

1585-1590 Alvaro Manrique de Zuniga Marques de Villamanrique

1590-1595 Luis de Velasco (the younger)

1595-1603 Gaspar de Zuniga y Acevedo, Conde de Monterrey

1603-1607 Juan de Mendoza y Luna Marques de Montesclaros

1607-1611 Luis de Velasco (the younger), Marques de Salinas

1611-1612 Garcia Guerra, Arzobispo de Mexico

1612-1621 Diego Fernandez de Cordoba Marques de Guadalcazar

1621-1624 Diego Carrillo de Mendoza y Pimentel Marques de Gelves y Conde de

Priego

1624-1635 Rodrigo Pacheco y Osorio, Marques de Cerralvo

1635-1640 Lope Diaz de Armendariz, Marques de Cadereyta

1640-1642 Diego Lopez Pacheco Cabrera y Bobadilla Marques de Villena y Duque de

Escalona, Grande de Espana

1642 Juan de Palafox y Mendoza, Obispo de Puebla

1642-1648 Garcia Sarmiento de Sotomayor Conde de Salvatierra y Marques de

Sobroso

1648-1649 Marcos de Torres y Rueda, Obispo de Yucatan

1650-1653 Luis Enriquez y Guzman Conde de Alba de Liste y Marques de Villaflor

1653-1660 Francisco Fernandez de la Cueva Duque de Alburquerque, Grande de

Espana

1660-1664 Juan de Leyva y de la Cerda Marques de Leyva y de Ladrada, Conde de

Banos

1664 Diego Osorio de Escobar, Obispo de Puebla

1673 Antonio Sebastian de Toledo, Marques de Mancera

1673 Pedro Nuno Colon de Portugal Duque de Veragua y Marques de Jamaica

1680 Payo Enriquez de Rivera, Arzobispo de Mexico

1680-1686 Tomas Antonio de la Cerda y Aragon Conde de Paredes y Marques de la

Laguna

1686-1688 Melchor Portocarrero Lasso de la Vega Conde de Monclova

1688-1696 Gasper de Sandoval Silva y Mendoza Conde de Galve

1696-1701 José Sarmeinto Valladares Conde de Moctezuma y de Tula, Grande de

Espana

1701 Juan de Ortega y Montanez, Arzobispo de Mexico

1701-1711 Francisco Fernandez de la Cueva Enriquez Duque de Alburquerque y

Marques de Cuellar

1711-1716 Fernando de Alencastre Norona y Silva Duque de Linares

1716-1722 Baltasar de Zuniga y Guzman Marques de Valero y Duque de Arion

1722-1734 Juan de Acuna, Marques de Casafuerte

1734-1740 Juan Antonio Vizarron y Eguiarreta Arzobispo de Mexico

1740-1741 Pedro de Castro y Figueroa Duque de la Conquista y Marques de Gracia

Real

1742-1746 Pedro Cebrian y Agustin, Conde de Fuenclara

1746-1755 Francisco de Guemes y Horcasitas Conde de Revilla Gigedo I

1755-1760 Agustin Ahumada y Villalon Marques de las Amarillas

1760 Francisco Cagigal de la Vega

1760-1766 Joaquin de Montserrat, Marques de Cruillas

1766-1771

Carlos Francisco de Croix, Marques de Croix

1766-1771

Carlos Francisco de Croix, Marques de Croix

1771-1779 Antonio María de Bucareli y Ursua

1779-1783 Martin de Mayorga

AFTER TREATY OF PARIS 1783

1783-1784 Matias de Galvez

1785-1786 Bernardo de

Galvez, Conde de Galvez

1787 Alonso Nuñez de Haro y Peralta, Arzobispo de Mexico

1787-1789 Manuel Antonio Flores

1789-1794 Juan Vicente de Guemes Pacheco y Padilla, Conde de Revilla Gigedo II

1794-1798 Miguel de la Grua Talamanca y Branciforte, Marques de Branciforte

1798-1800 Miguel José de Azanza

1800-1803 Felix Berenguer de Marquina

Viceroys During the Mexican War for

Independence

1803-1808 José de Iturrigaray

1808-1809 Pedro Garibay

1809-1810 Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont, Arzobispo de Mexico

1810-1813 Francisco Javier de Venegas

1813-1816 Felix María Calleja del Rey

1816-1821 Juan Ruiz de Apodaca, Conde del Venadito

1821 Francisco Novella

1821 Juan de O’Donoju (appointed without taking office)